Data On Traps Part 2: Levator vs Upper Traps

n1 training

Does the evidence support the claims?

Is there really a mountain, metric ton, or butt load of evidence that the levator scapulae is the prime mover of a shrug, followed by the middle delts, and that upper traps are better trained with rows?

In addition to the Castelein 2015 paper, I gathered about 80 papers that I thought might have some relevance. After reading them, about 30 had some relevance, but only 9 were contextually relevant enough in my opinion. 4 of them I had to purchase the full text. You know I’m something of a scientist myself, but zero studies directly looked at the questions in the context of resistance training for hypertrophy.

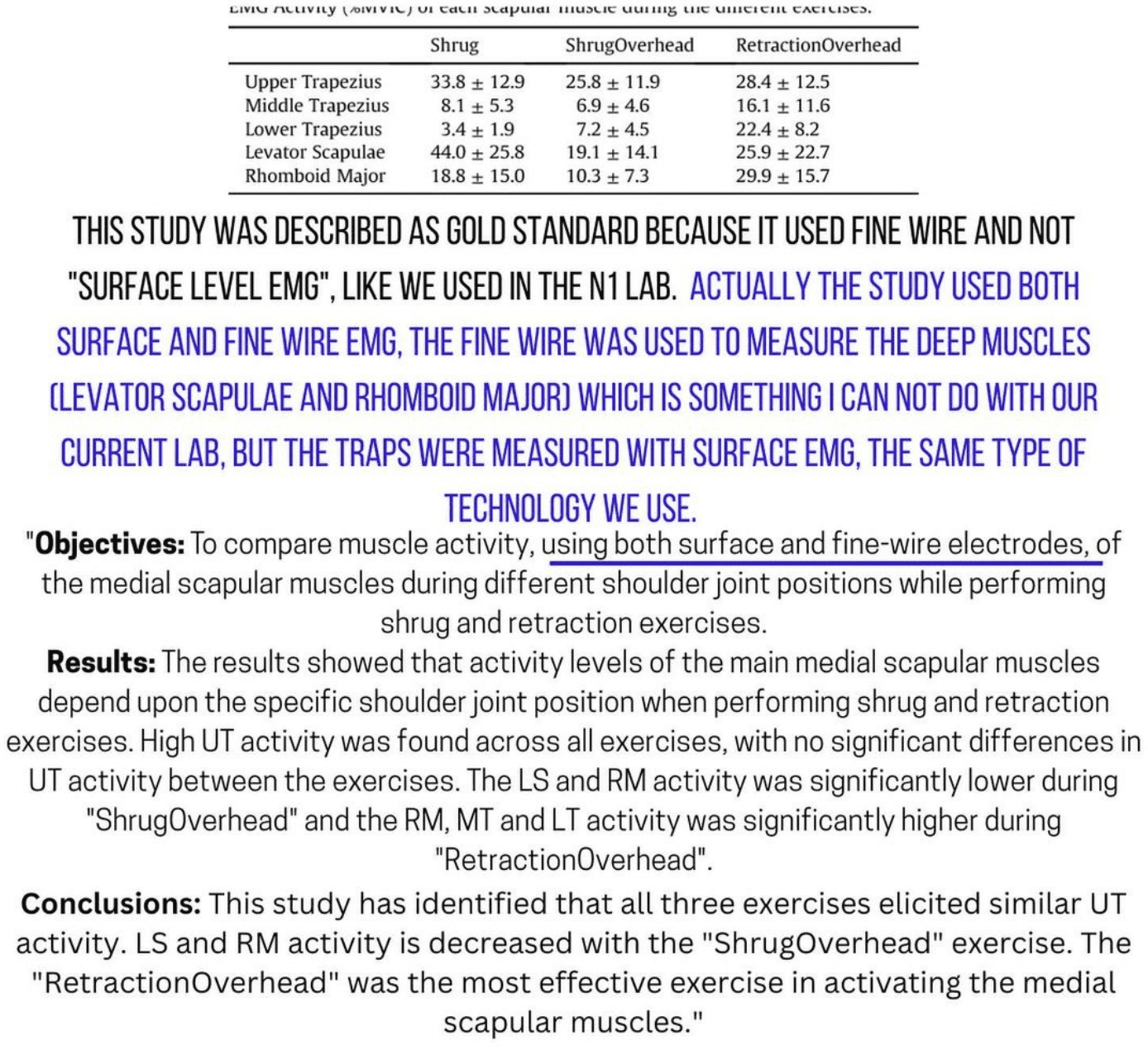

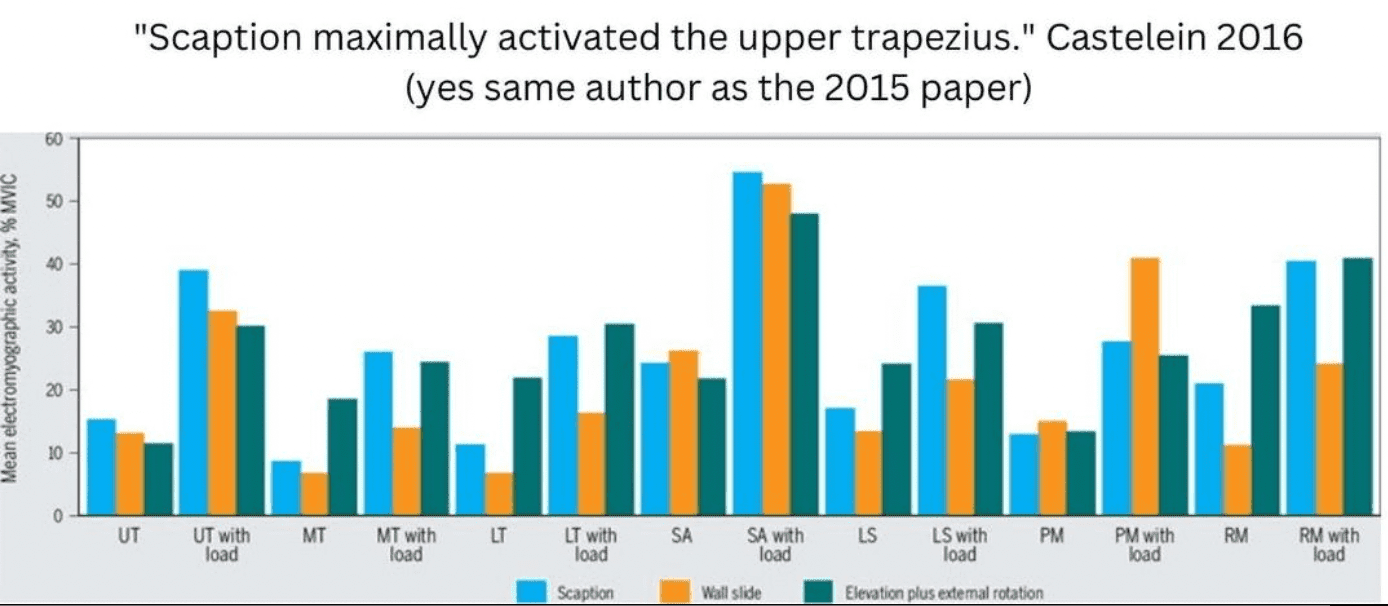

Let’s start with the Castelein et al 2015 results that were posted in the video making the claims.

Additionally the claim was made that in this “gold standard” study, they didn’t measure the upper traps properly. And, instead the upper trapezius results should be interpreted as middle trapezius results.

If we assume the researchers did actually measure the upper traps. The regular shrug highest for both the levator and the upper trapezius. If we assume that they placed the sensors incorrectly to measure the upper traps, then we can’t make any conclusions for upper traps from this study, and also in regards to the middle traps, how do we resolve the conflicting results between the original middle measurement and the incorrect upper trap sensor?

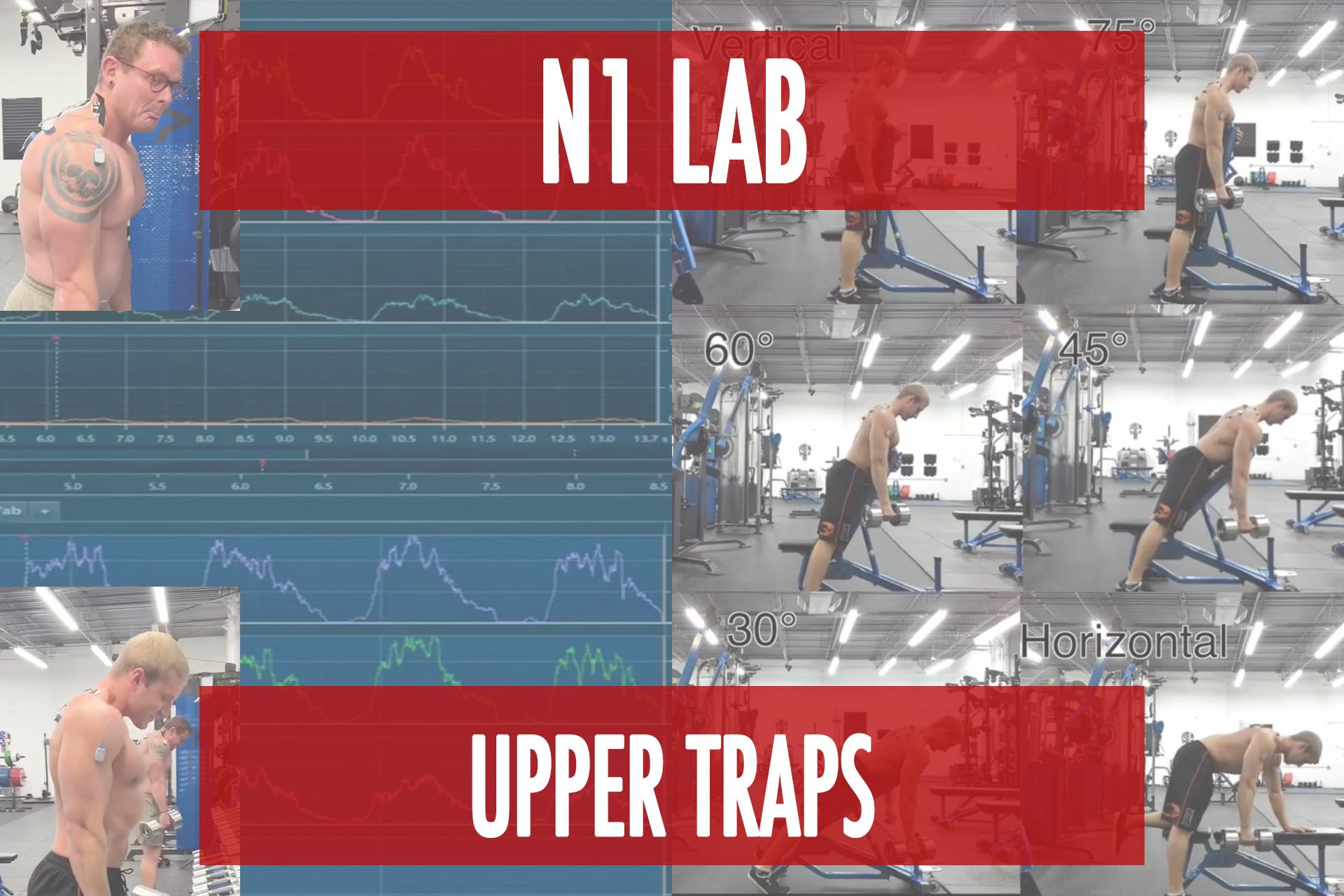

At best we could guess that higher fibers are more active in standard shrugging, but would logic not continue to the upper traps? This is exactly why we ran the N1 Lab where we placed the sensors on the upper traps that were clearly on the clavicular fibers and not the middle traps. We also measured the middle traps on the inferior side of the line from the C7 to the acromion to ensure it was only middle trap and we found all 3 were higher in more vertical shrugging.

If we report that data as a ratio, you see the ratio of upper traps higher in the more vertical motions in a mechanically predictable manner.

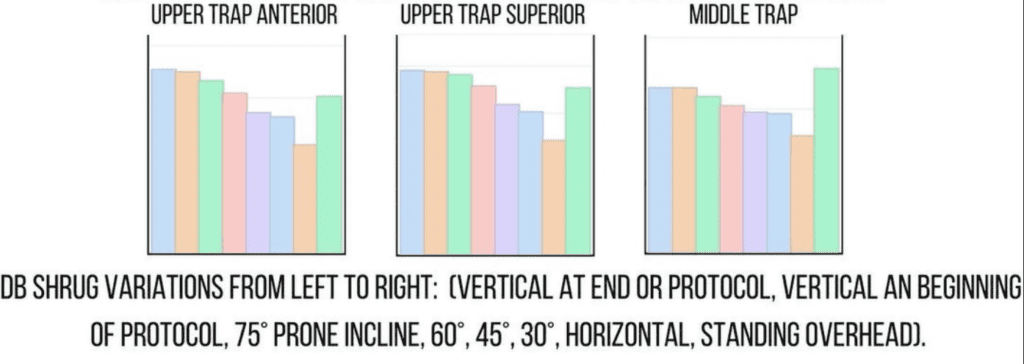

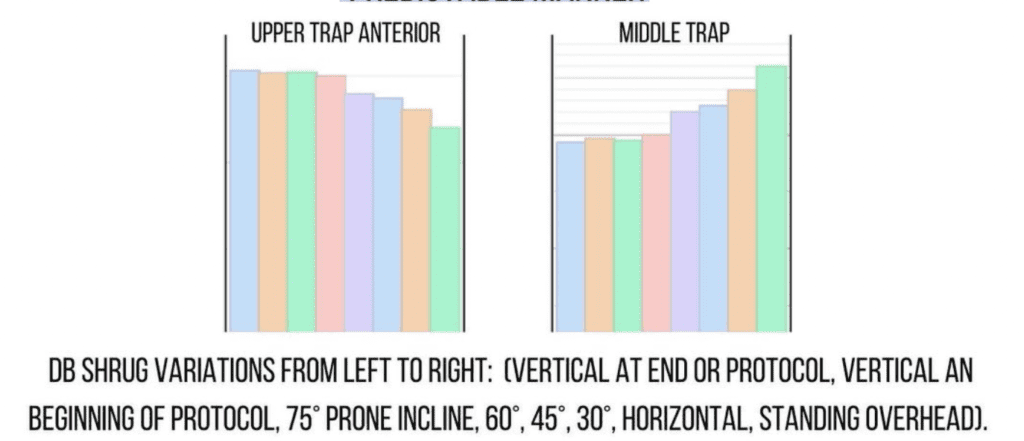

In this chart from Anderson et al 2011, you can see a similar trend in the upper: middle trap ratio where the more vertical loading patterns are biased to the upper traps.

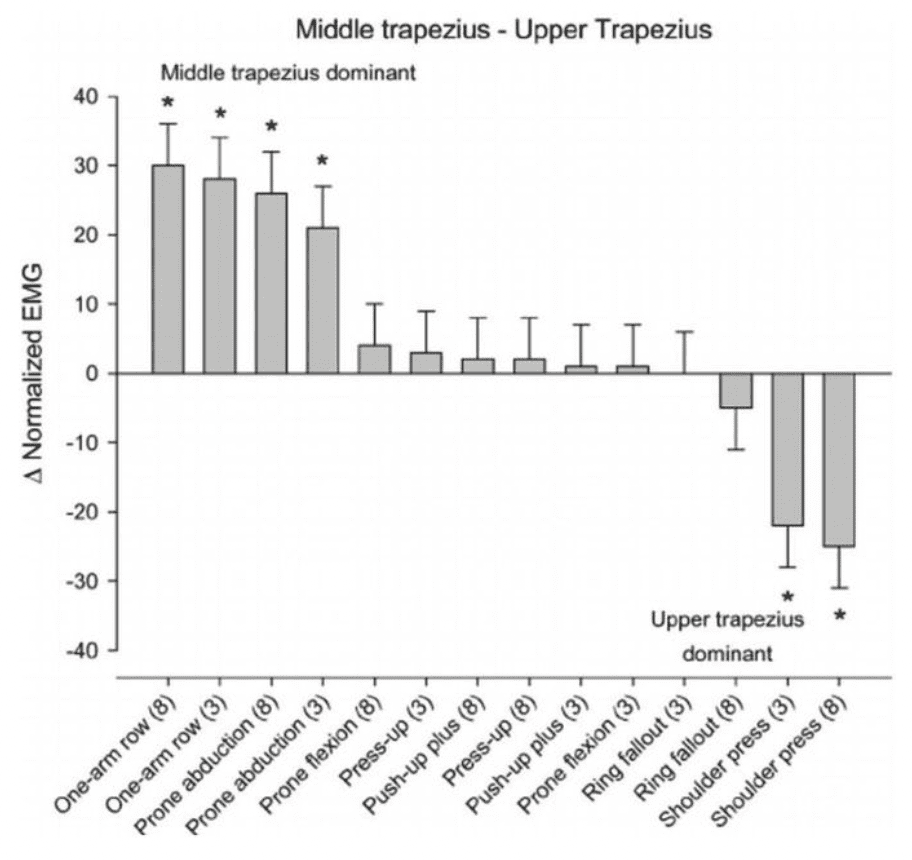

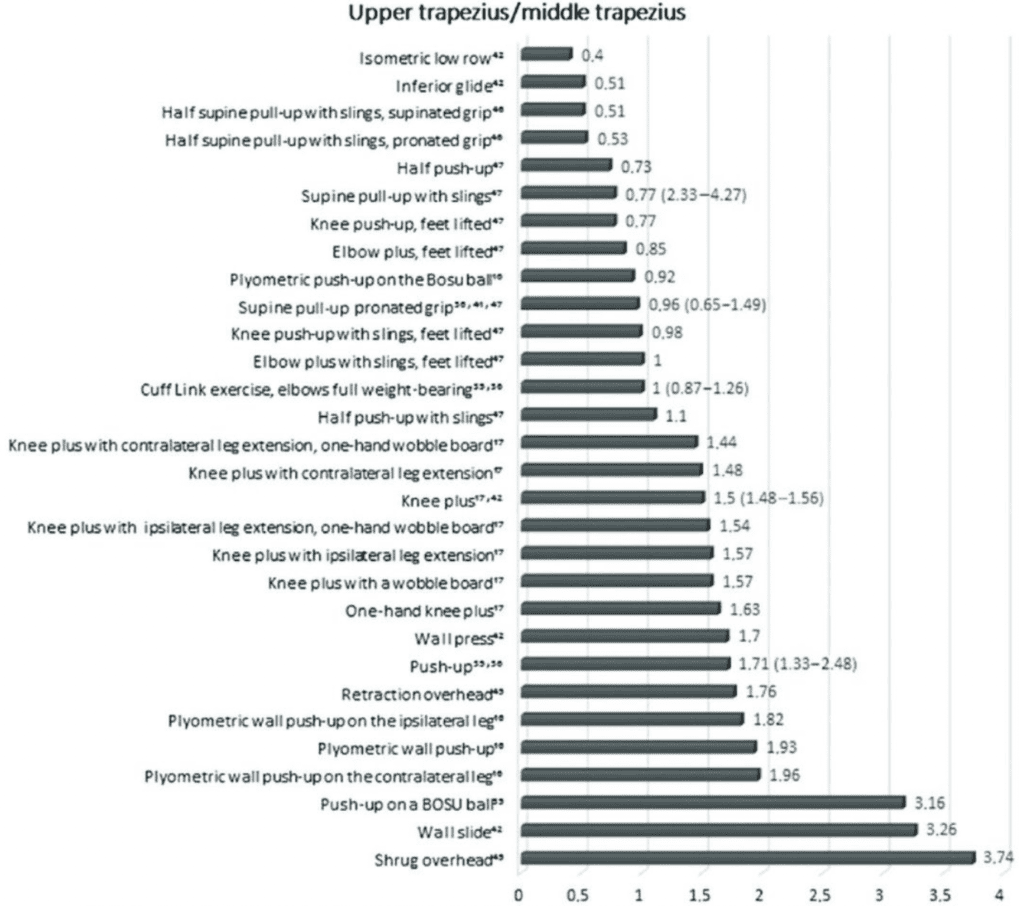

The 2019 systemic review from Karabay et al also reported a similar trend with the most upper trap biased being an overhead shrug, and the most middle trap a rowing motion.

The consistent results I found reading these studies aligned with our finding at N1, in that both the upper and middle traps work in elevating the shoulder, but the upper traps are biased more in vertical motions, and as you become more horizontal that bias shifts towards the middle traps.

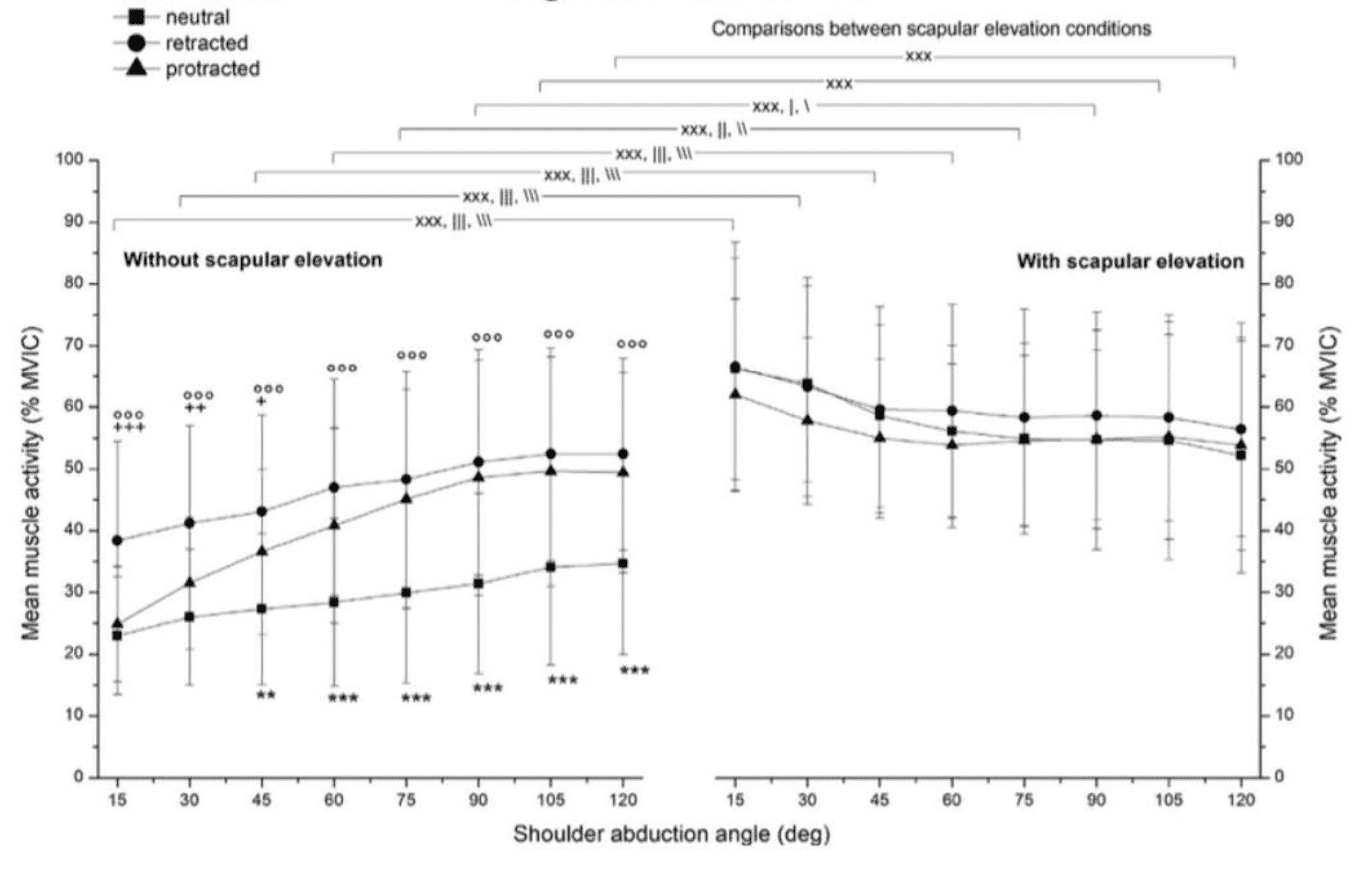

Another 2019 study (a big year for traps I guess) Contemori et al. looked at effects of scapular retraction/protraction position and scapular T elevation on shoulder girdle muscle activity during glenohumeral abduction. Their results:

“Scapular retraction led to higher activation of the entire trapezius muscle, whereas protraction induced higher upper trapezius, middle deltoid and serratus anterior activity, along with lower activity of middle and lower trapezius. Shoulder elevation led to higher activity of the upper trapezius and middle deltoid. Moreover, it induced lower activation of the serratus anterior and middle and lower trapezius, thus leading to high ratios between the upper trapezius and the other scapulothoracic muscles, especially between 15 and 75 degrees of abduction.”

So the notion that the upper traps would be better trained in a row isn’t supported in any of these EMG studies, in fact doing the opposite (protraction) had the highest UT:MT ratio in the study. This doesn’t say protraction is a better way to train the upper traps. But adds more evidence that the middle traps would be the ones that are more biased when retraction is a greater part of the motion.

I know the lab work I do has its limitations. I can’t remove my bias and it’s not peer reviewed. But I do video sync all our data collection, so unlike much of the research, if I post something based on our specific test you can see exactly what we are doing synced with the raw data. I hope that the transparency of that counts for something. I also know that I’m not going to run 100 people through a study, but I do know that we are testing the exact population we are interested in. Strong, lean, well trained individuals that have good technique.

Lastly, I know we have done extensive research and trials on our methods and secured top of the line hardware. The main purpose of the N1 lab is for us to have something to fill in the gaps between well done published research, and the real work application and specific exercises we are using. Our conclusions are always based on the totality of available evidence. In this instance the “mountain” of evidence seems to align with our lab findings.

Hopefully at this point, between clearing up the anatomical study and quickly looking at the EMG data we can agree that shrugging type motions near vertical are going to be good for training the upper traps. Who’s surprised?

But what about the levator? It seems like it would get trained in shrugs too? Is it the prime mover and upper traps are second.

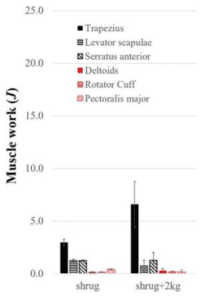

Yet another 2019 paper, Muscle contributions to the upper-extremity movement and work from a musculoskeletal model of the human shoulder by Seth et al (it really was the year of the traps). Random factoid, that’s also when my trap bar design from Prime came out. Anyway they used a computation model to estimate the actual “work” being done by these muscles during a shrug with 2kg of resistance and you can see the levator is not contributing much especially as the loading was added. This chart I believe only represents the middle trapezius, and not even the clavicular fibers, so in my opinion it’s an underestimation of how much more the traps are contributing.

Why is this? Even though the levator is highly active in a shrug, it doesn’t mean it is the muscle producing the majority of the forces for the exercise. The levator being attached to the medial side of the scapula and being relatively small are going to limit its contribution to the shrug forces.

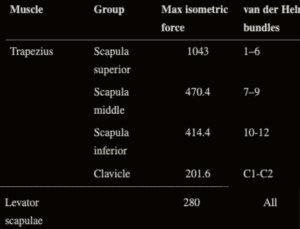

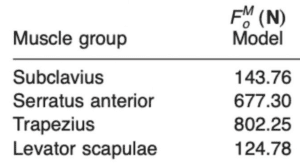

An earlier study estimation of musculotendon properties in the human upper limb. Garner 2003 also models the levator as having a much lower force capacity than the trapezius, although it’s not broken up by divisions.

However, from anatomical studies we know that the upper and middle traps are going to make up a little over 50% of that, so maybe by this estimate the traps with orientation to shrug would have little more than 3x the force capacity with a overall better leverage except for the lowest fibers of the middle trap.

All in all, I think we have substantial evidence to suggest while shrugs will train your levator that it is going to be the traps that are really the prime movers. Similar to how doing horizontal hip abduction is going to work the piriformis, so it’s a good way to train it, but the superficial muscles like the glute medius is actually going to be producing more of the force.

This will always be the reality for some of these deep small muscles that are more responsible for managing the joint while larger muscles are generating the torque to produce the movement.

So what can we apply in the gym from all of this?

Training recommendations covered in Part 3

Popular Pages

Learn & Train With Us

Add N1 Training to your Homescreen!

Please log in to access the menu.