What is Training to Failure?

n1 training

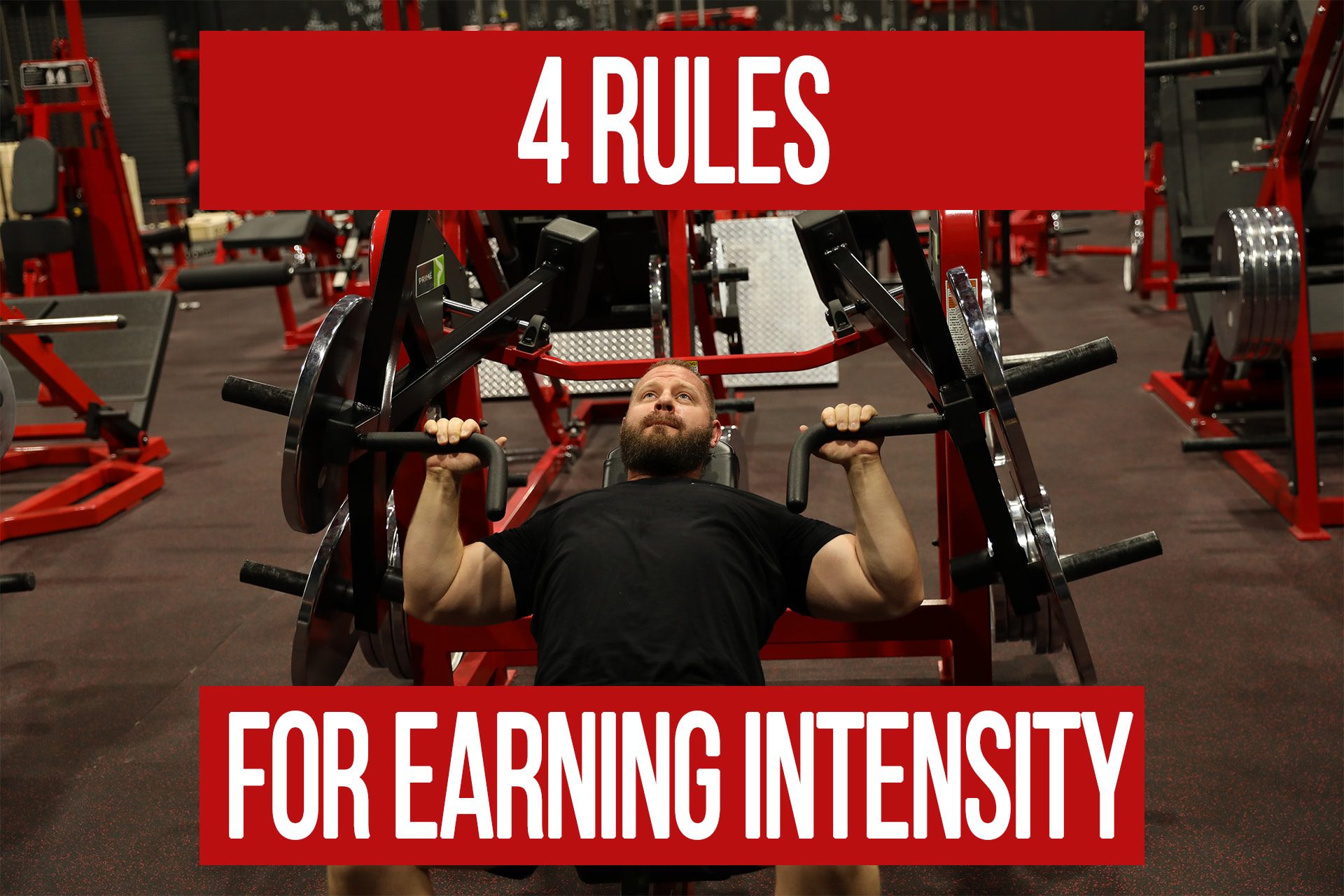

The phrase “training to failure” is used often, but not very precisely. When you are trying to maximize every set, it’s important to know the desired outcome you have. This allows for consistency and overall better results. If you nearly gauge the level of failure by your perceived level of fatigue, it will be extremely variable depending on the exercise, your energy that day, nutrition status etc.

It also makes it very difficult for coaches to prescribe a training level based on your perceived level exhaustion.

A better way is to have a set of principles that outline the process of training to failure.

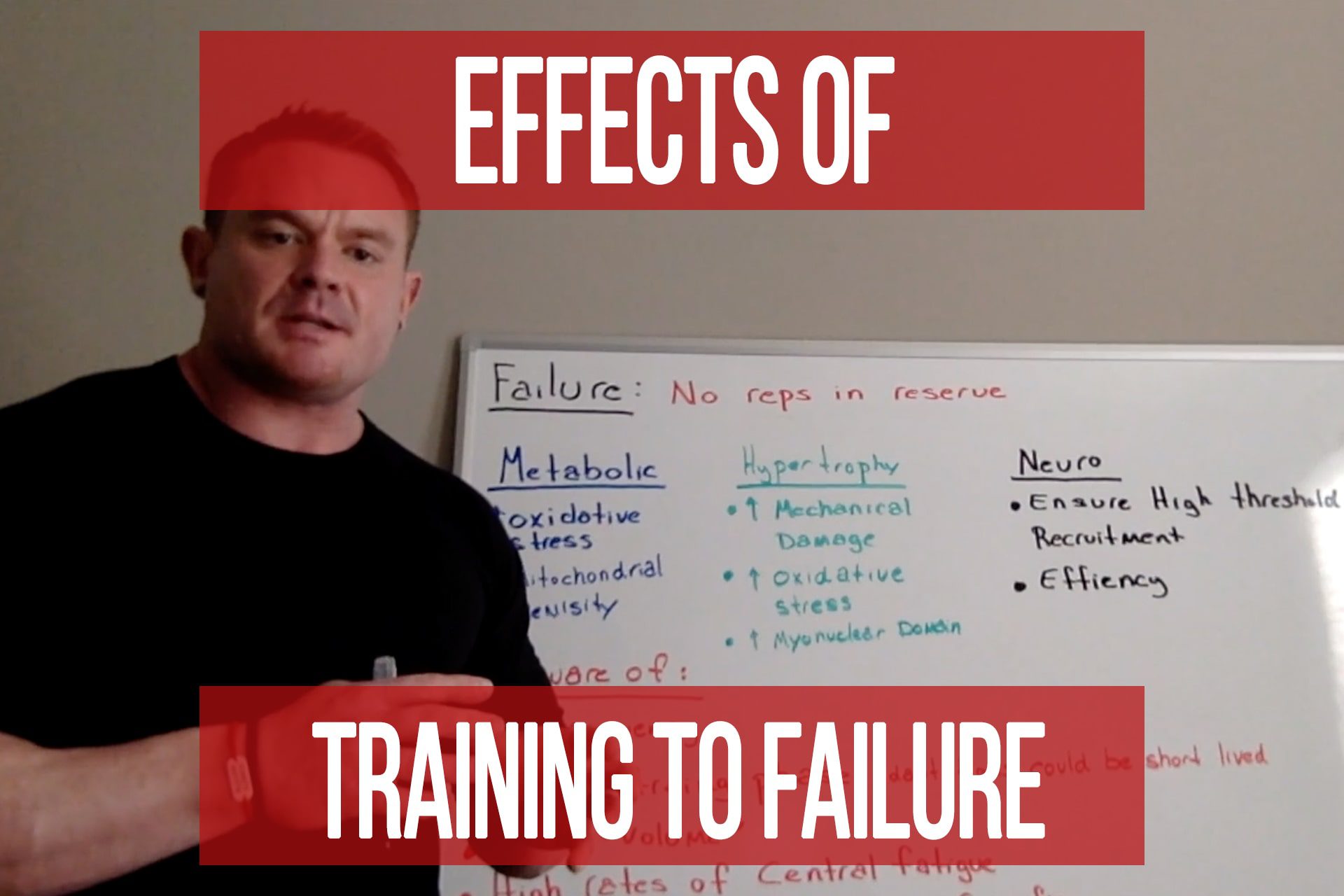

Terms of Failure:

Positive Failure: Defined as the the last rep you can complete before losing any form or range of motion at the given weight you started with. Form includes tempo, so you must be able to control the speed of the weight, as well as controlling what muscles are doing the work.

Complete Failure: Defined as pushing past the range of motion barrier to where you can no longer move the weight in the desired exercise even with some changes in tempo or loss of range of motion. There is grey area into how much loss of form is allotted for, but the only acceptable complete failure methods I suggest are loss of range of motion, and maybe a minimal amount of tempo or recruitment.

In other words, if you are doing a set of bicep curls, it is better to force some reps where you can not get the weight all the way up and just go back down and do a few more controlled partial reps than it is to swing the weight from the bottom and then drop it fast. Losing some range of motion but still contracting the working muscle, and controlling it allows you to fatigue that working muscle further. Adding your hips and back into a bicep curl does not help work the bicep, it may increase the amount of mechanical damage due to more eccentric work but it also increases your risk of injury.

Extended Failure: Defined as following the rules of positive failure, but repeating efforts without rest, after decreasing the resistance. A classic example is a drop set. The form, and range of motion should not decline. The resistance is just decreased once positive failure is reached, and then more reps are perfumed until positive failure is reached again. There is not a limit on number of resistance drops you can use, but there is a point of diminishing returns where you reach a resistance that is too low to provide any physiological benefit.

It also depends on what the desired stimulus of the set is. Continuing to drop weight and perform reps will push you into an oxidative training stimulus. This is usually evident by a sudden increase in the number of reps you are able to perform at the reduced resistance relative to your first drop in weight. That is not always bad, but something to be aware of if that is not the goal of the workout.

Neurological Failure: Defined as the point where your nervous system performance and the intensity of your contractions begins to decline. This is usually marked by a decrease in concentric speed as your sets progress. It is absolutely essential that execution of each rep is at its best when training for a neurological-focused goal. If your execution or the speed of contractions begin to decline, chances are that you’ve tapped out your nervous system for that workout and further work may be counterproductive.

You are not always going to be training to failure, but it is important that each set you know how far you are going to take it when you do. This leaves you mentally prepared, and physically because you will choose the correct amount of resistance, and get the correct number of reps every set.

The phrase “train to failure” is used often, but not very precisely. When you are trying to maximize every set, it’s important to know the desired outcome you have. This allows for consistency and overall better results. If you nearly gauge the level of failure by your perceived level of fatigue, it will be extremely variable depending on the exercise, your energy that day, nutrition status etc.

It also makes it very difficult for coaches to prescribe a training level based on your perceived level exhaustion.

A better way is to have a set of principles that outline the process of training to failure.

Defining Terms of Failure

You are not always going to be training to failure, but it is important that each set you know how far you are going to take it when you do. This leaves you mentally prepared, and physically because you will choose the correct amount of resistance, and get the correct number of reps every set.

For more tips on upgrading your training, be sure to check out the 400+ other articles and videos in the member’s area.

Please Log In to Submit Your Question

Understanding Training to Failure Part 1

videoBody Composition FREE Hypertrophy Program Design Strength & Power Training

Popular Pages

Learn & Train With Us

Add N1 Training to your Homescreen!

Please log in to access the menu.