Junk Volume is unnecessary work that only slows down progress.

Well as far as #1 is concerned, this actually requires you to know what the specific goal of your workout is. That will determine what qualities and relative intensities the sets need to contain in order to contribute to that goal.

It does not mean that anything submaximal is “junk” as in some cases, for example if using an incomplete rest method, that accumulation of submaximal work is contributing to the stimulus. On the other hand, if your goal is neurological intensity for a strength-focused goal, then only sets above a certain threshold of intensity will contribute to that. In that case sets that are too low intensity will be considered junk volume as they only add to your accumulation of fatigue which will ultimately decrease your maximum potential force output, which is the goal of the workout. So not only does it not help you, it can actually inhibit your ability to accomplish what you need to.

Now, let’s assume you have accomplished the goal stimulus of the workout, whatever that might be. Any sets or additional work done past that is also junk volume. At a certain point additional sets will only increase the demands on your recovery without contributing any additional benefit. This is where we look at something called trainability, which is a major focal point of the Nutrition & Program Design course, but here is the summary:

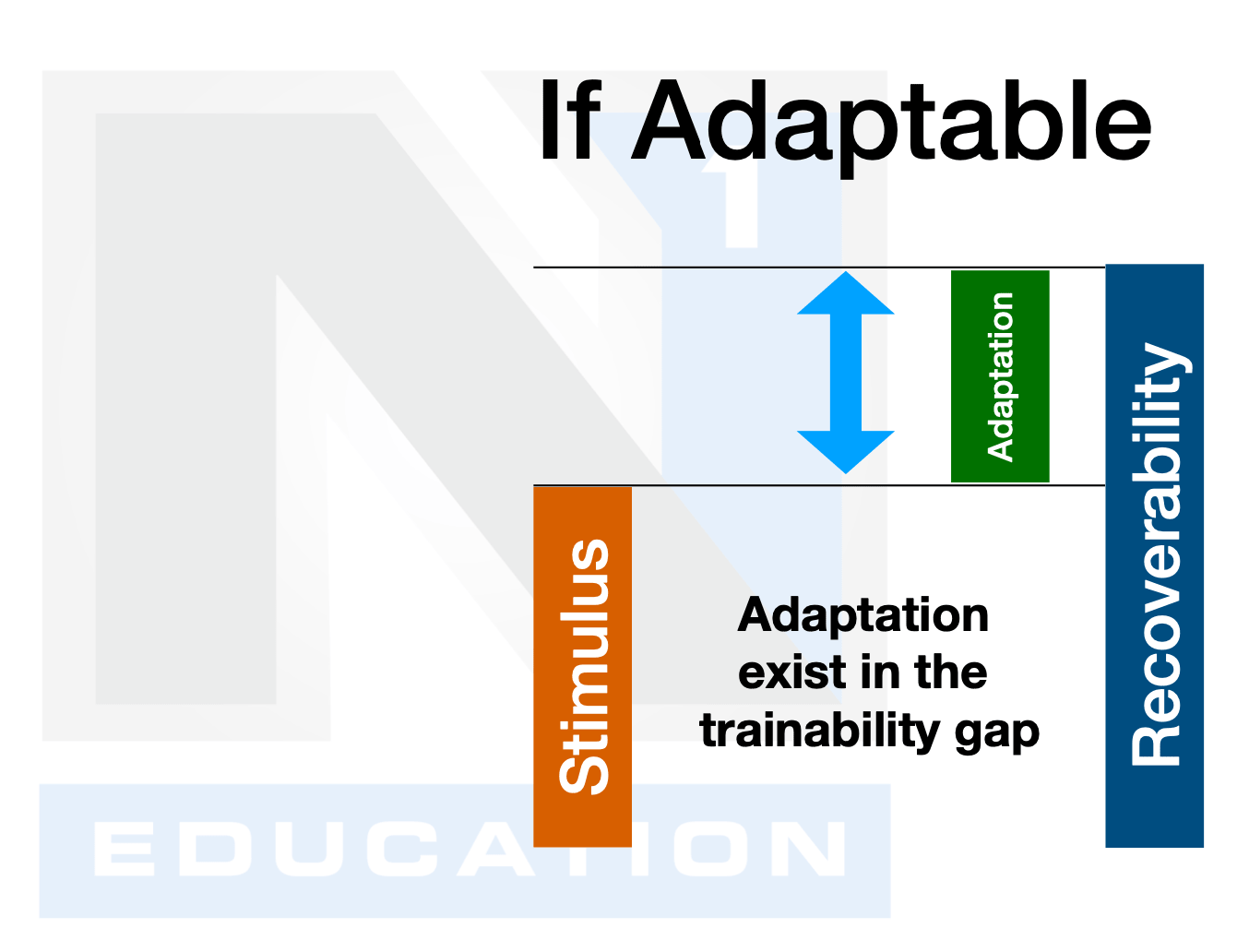

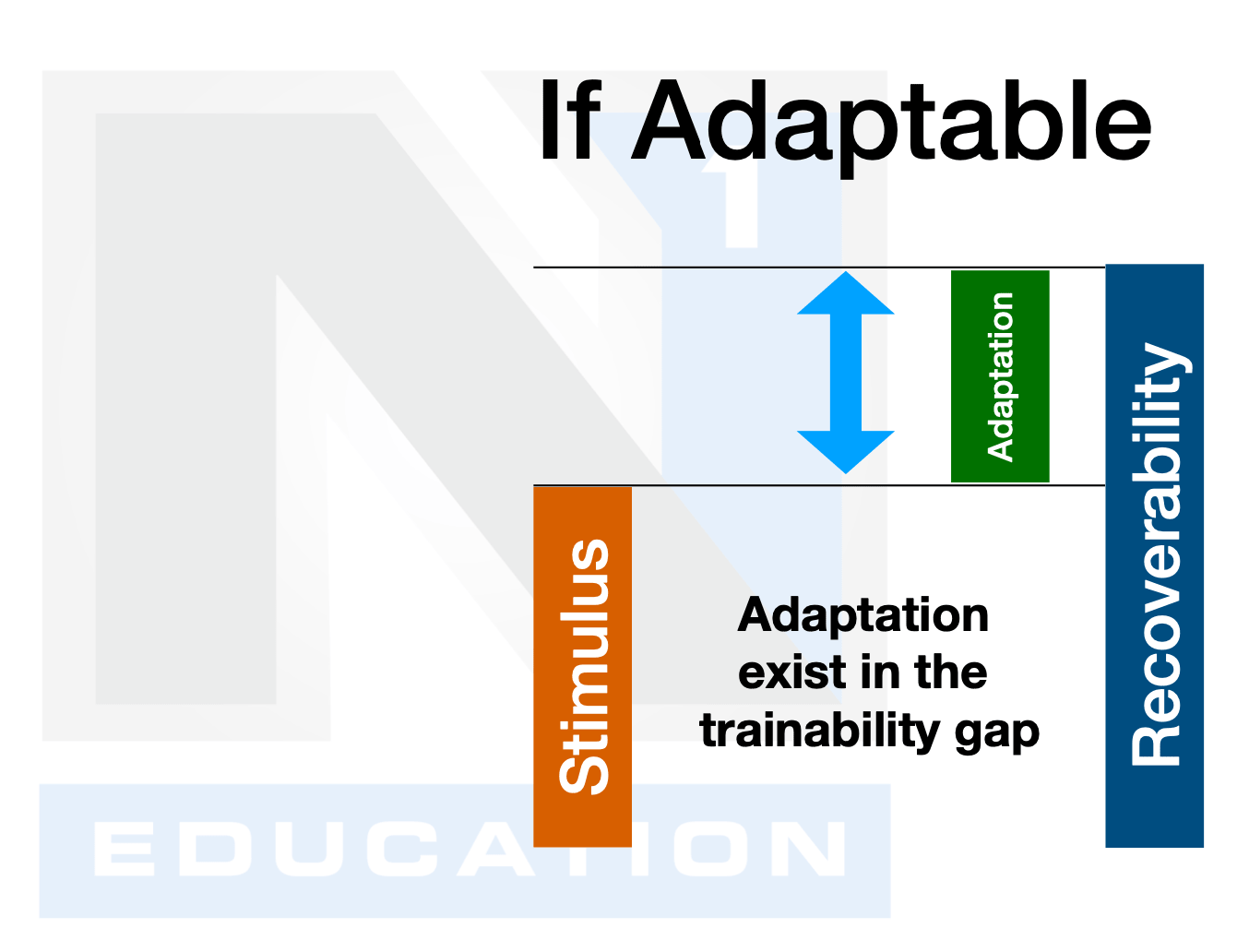

There is a given amount of work required to achieve a specific stimulus. You must work up to or slightly past that threshold in order to elicit an adaptation response in order to make progress. You also have a maximum tolerable level of work you can recover from. The difference between the two is referred to as your trainability. The goal is to have the work done in your training slightly surpass the threshold for adaptation while staying below your maximum recoverability.

If you continue to add sets or work past your ability to recover, this “junk volume” slows down your recovery time, increases stress on your body unnecessarily, and if too far in excess may actually take you a step backward.

So your goal is to stimulate the desired adaptation with your training and use the minimum effective dose to achieve the stimulus threshold so that you can recover as easily as possible. Faster recovery means you can train more frequently and it gives you more room to progressively overload over time. Trying to do too much too fast will have the opposite effect and you’ll find that you’ll plateau very quickly.

An easy example of this is for a neurological intensity goal. Once you hit failure or peak output you’re done. Any additional sets of that exercise will only be submaximal and will only be contributing to increased fatigue and require more recovery. More on that in THIS VIDEO.

This is why we advocate for focusing on maximizing recoverability and rotating between stimuli as-needed. There is a different trainability gap for different stimuli, so periodizing them appropriately allows you to continue to progress even once you have stopped adapting to one. De-load or take a short break from a specific stimulus and over time the threshold required to get that adaptation will decrease. Then you can jump back in to it to continue progressing at a faster pace.

If you want to get more in depth with programming, periodization, trainability, matching nutrition to stimuli and more, check out the N1 Nutrition & Program Design for Trainability course. This is basically a university-level course in about 25 hours of content.

Junk Volume: Sets that either (1) do not contribute to the goal stimulus of the workout or (2) that are in excess of your recoverability.

As far as #1 is concerned, this actually requires you to know what the specific goal of your workout is. That will determine what qualities and relative intensities the sets need to contain in order to contribute to that goal.

It does not mean that anything submaximal is “junk” as in some cases, for example if using an incomplete rest method, that accumulation of submaximal work is contributing to the stimulus. On the other hand, if your goal is neurological intensity for a strength-focused goal, then only sets above a certain threshold of intensity will contribute to that. In that case sets that are too low intensity will be considered junk volume as they only add to your accumulation of fatigue which will ultimately decrease your maximum potential force output, which is the goal of the workout. So not only does it not help you, it can actually inhibit your ability to accomplish what you need to.

Now, let’s assume you have accomplished the goal stimulus of the workout, whatever that might be. Any sets or additional work done past that is also junk volume. At a certain point additional sets will only increase the demands on your recovery without contributing any additional benefit. This is where we look at something called trainability, which is a major focal point of the Nutrition & Program Design course, but here is the summary:

There is a given amount of work required to achieve a specific stimulus. You must work up to or slightly past that threshold in order to elicit an adaptation response in order to make progress. You also have a maximum tolerable level of work you can recover from. The difference between the two is referred to as your trainability. The goal is to have the work done in your training slightly surpass the threshold for adaptation while staying below your maximum recoverability.

If you continue to add sets or work past your ability to recover, this “junk volume” slows down your recovery time, increases stress on your body unnecessarily, and if too far in excess may actually take you a step backward.

So your goal is to stimulate the desired adaptation with your training and use the minimum effective dose to achieve the stimulus threshold so that you can recover as easily as possible. Faster recovery means you can train more frequently and it gives you more room to progressively overload over time. Trying to do too much too fast will have the opposite effect and you’ll find that you’ll plateau very quickly.

An easy example of this is for a neurological intensity goal. Once you hit failure or peak output you’re done. Any additional sets of that exercise will only be submaximal and will only be contributing to increased fatigue and require more recovery. More on that in THIS VIDEO.

This is why we advocate for focusing on maximizing recoverability and rotating between stimuli as-needed. There is a different trainability gap for different stimuli, so periodizing them appropriately allows you to continue to progress even once you have stopped adapting to one. De-load or take a short break from a specific stimulus and over time the threshold required to get that adaptation will decrease. Then you can jump back in to it to continue progressing at a faster pace.

If you want to get more in depth with programming, periodization, trainability, matching nutrition to stimuli and more, check out the N1 Nutrition & Program Design for Trainability course. This is basically a university-level course in about 25 hours of content.

Please Log In to Submit Your Question

Please log in to access the menu.