Leg Extension VS Barbell Squat (Updated)

n1 training

Leg Ext vs Barbell Squat

While both exercises train the quads, the range of motion and other factors vary greatly between the leg extension and barbell squat.

Barbell Squat

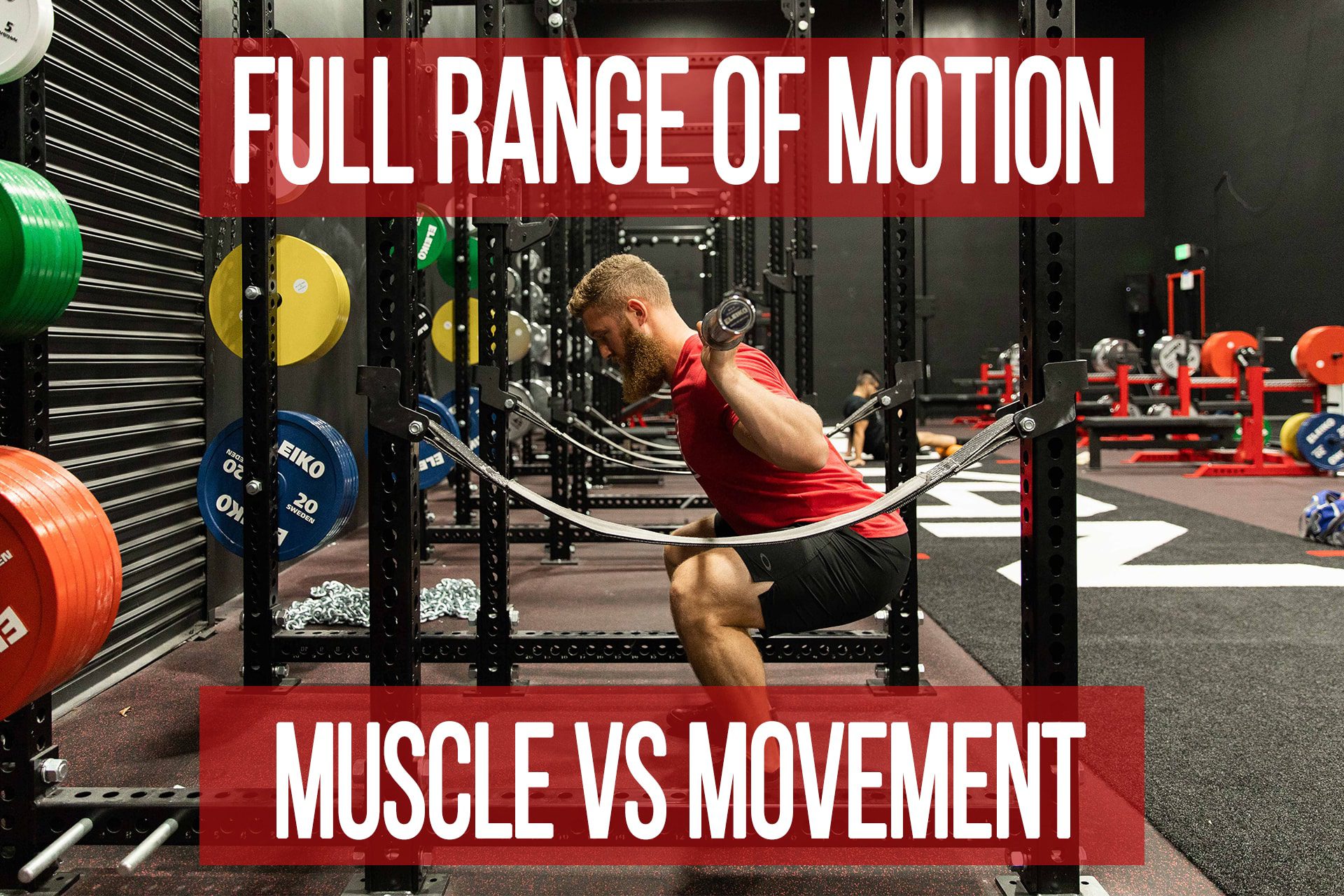

Range of Motion

The barbell squat is going to work the lengthened position of all the quads except the rectus femoris, both in terms of muscle length and resistance profile. This means it can be a great tool for creating mechanical damage or training for strength focused goals, depending on how you program it.

It also incorporates hip movement, so you can use glutes and adductors as synergists, which will also increase the systemic metabolic demand of the exercise compared to the leg extension.

If you are not able to reach full knee flexion in a traditional barbell squat (while maintaining a neutral spine), there is the option of using a heel elevation. Heel wedges can simulate having more ankle flexion and longer tibias, allowing you to get greater knee flexion before ankle or hip flexion become your limiting factor.

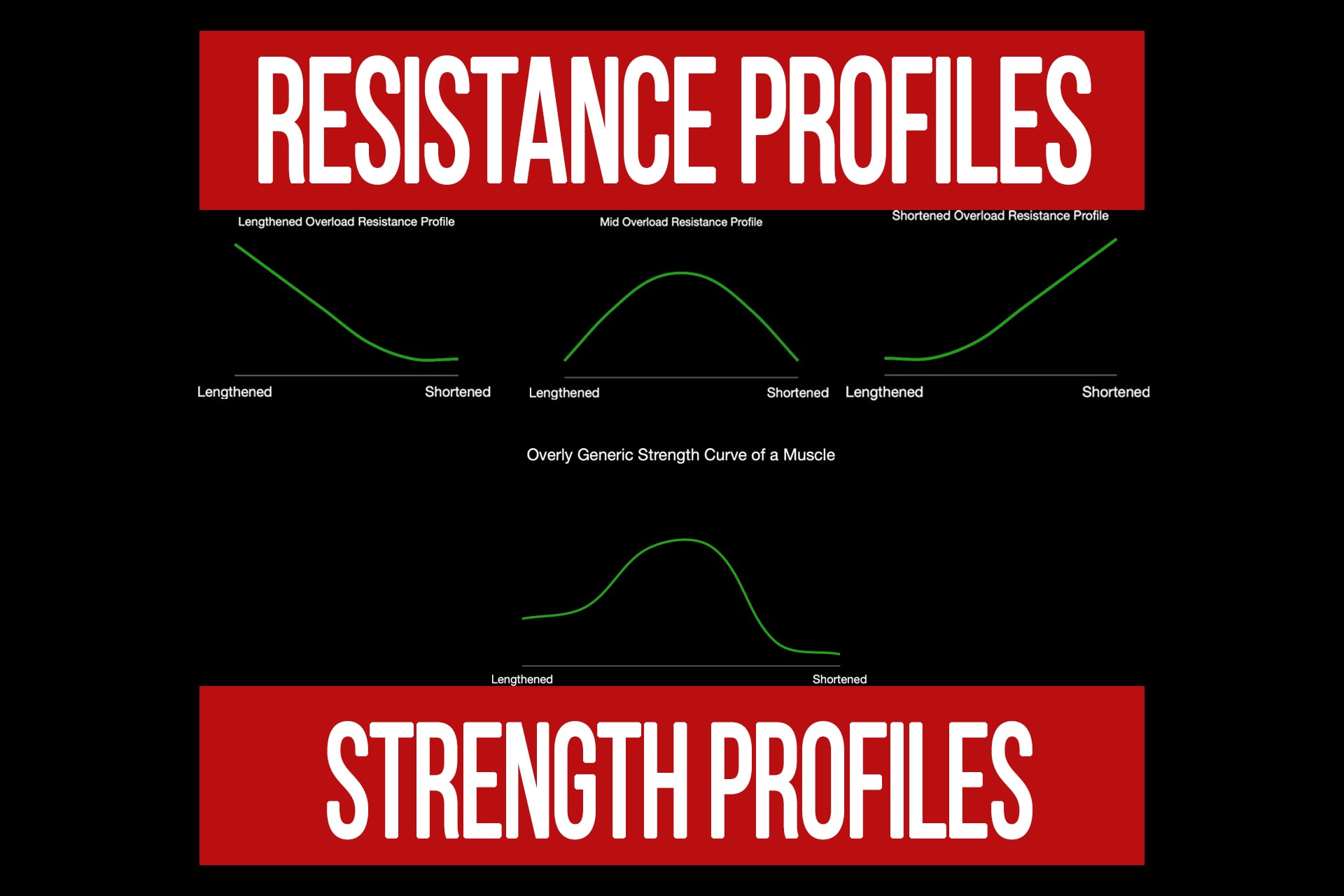

Resistance Profile

The barbell squat is overloaded at the bottom of the rep, in the lengthened position for the quads and hip extensors. While we can shift it slightly by utilizing bands or chains, those can add degrees of complexity and coordination needed to perform this movement.

Training Stimuli

Overloading the lengthened position of a muscle increases the potential for creating mechanical damage when taken close to failure and/or at higher volumes. This will affect the frequency with which you can train the quads and hip extensors as mechanical damage is one of the stimuli that takes relatively longer to recover from. To learn more about mechanical damage, read this article:

Mechanical Damage & Hypertrophy

Due to the large amount of tissue recruited in the squat (quads, glutes, adductors, etc.) it can be very systemically taxing. If your goal is improving systemic conditioning (cardiovascular, cardiorespiratory, liver metabolism of metabolic byproducts, etc) this can be a useful tool. For more on systemic training read this article:

Set & Rep Methods: Systemic Super Sets

Safety

The safety consideration for the barbell squat is making sure to respect your active range of motion for hip flexion. This means maintaining a neutral spine and not letting your spine begin to round or pelvis tilt at the bottom. This is the primary cause of injury in the barbell squat.

Because the squat does require a relatively high degree of coordination, taking it to the same degree of failure as a more isolated and stable exercise (like the leg extension) is extremely challenging. Depending on what tissue you’re using the squat for predominantly (quads, glutes, adductors), other tissues may reach failure first, limiting the maximum potential stimulus you can get from this exercise for the target tissue.

Fatigue may lead to a degradation in execution, increasing the risk of injury in those who have not mastered the ability to maintain their execution at high intensities and degrees of fatigue.

Other Considerations

The spine is also loaded in the barbell squat, which means there is demand placed on the spinal stabilizers like the erectors. This can affect what other exercises you choose in the rest of your program and how frequently you can use them. For example, doing a barbell squat followed by an RDL may decrease the load and volume you can tolerate in the RDL due to the fatigue of the spinal stabilizers.They may be the limiting factor rather than the hip extensors you’re trying to train with the RDL.

For more information on the barbell squat, check out the following pieces of content:

How to Determine Full Squat Depth

Leg Extension

Range of Motion

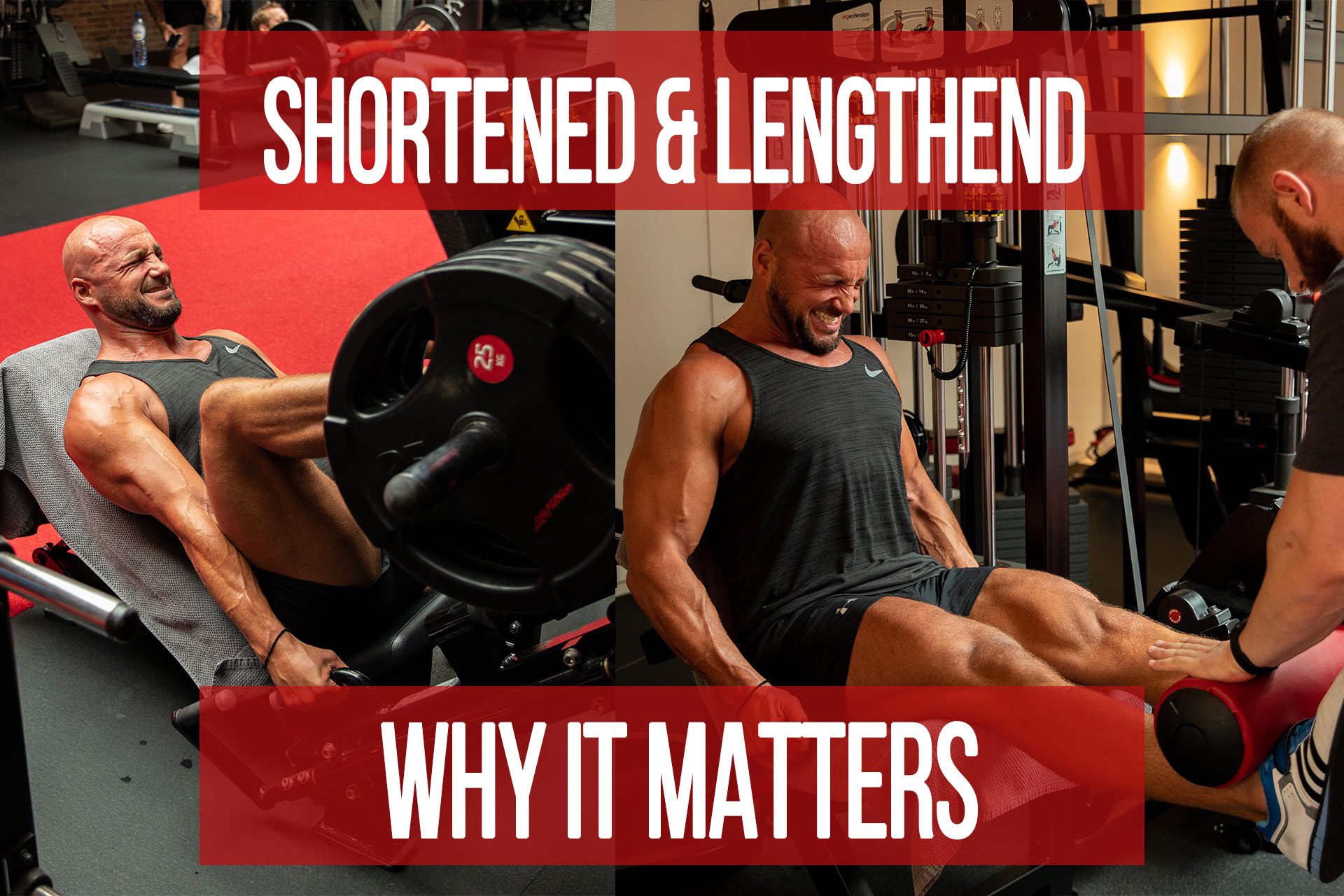

The leg extension will be the most isolated to the quadriceps as there is no hip movement. It will provide work in the fully shortened position in a way no other knee extension exercise provides.

Resistance Profile

Because it predominantly trains and overloads the short position, the leg extension is one of the top choices for metabolic programs. You can take it to a higher degree of fatigue and greater volume of work with less mechanical damage compared to most any other quad exercise.

Safety

The leg extension is a very safe place to work hard. So long as you’re following a proper tempo and not bouncing out of the bottom or failing to control the eccentric, you’re unlikely to harm yourself. You can literally keep working until you can no longer move.

Because your foot is essentially floating, the knee stability is limited especially in the lengthened position. So it’s best to adjust your resistance, intent, and tempo to get most of your work done in the short position for the leg extension.

This means it is not a great exercise for mechanical damage stimuli on it’s own. But when used as a pre-exhaust before something that trains the lengthened position (like the barbell squat), it is a brutal combination.

Other Considerations

The leg extension is about as isolated and stable of a quad exercise as it gets, making it a great choice for training the quads to a high degree of fatigue without other tissues or breakdown in execution becoming the limiting factor.

It can easily be paired with most other quad exercises to create a variety of super sets for various stimuli. Because the leg extension and barbell squat are essentially opposite in their resistance profiles, they can be a great compliment to one another in a program to maximally tax the quads through a greater range of motion than either can on its own.

Related Content:

https://n1.training/hip-flexion-leg-extension/

https://n1.training/leg-extension/https://n1.training/solo-wedge-squat-setup/

Introduction

The goal of these “versus” posts is not to say that one exercise is absolutely better than another. Rather, it is to give you some insight in to which exercise might be better suited for a particular situation or for a specific training stimulus.

Factors that we consider include resistance profiles, stability, overlapping muscle groups, range of motion, and more. The following considerations are intended to help you choose when and how to apply each exercise depending on your goal for the workout.

Barbell Squat

Range of Motion

The barbell squat is going to work the lengthened position of all the quads except the rectus femoris, both in terms of muscle length and resistance profile. This means it can be a great tool for creating mechanical damage or training for strength focused goals, depending on how you program it.

It also incorporates hip movement, so you can use glutes and adductors as synergists, which will also increase the systemic metabolic demand of the exercise compared to the leg extension.

If you are not able to reach full knee flexion in a traditional barbell squat (while maintaining a neutral spine), there is the option of using a heel elevation. Heel wedges can simulate having more ankle flexion and longer tibias, allowing you to get greater knee flexion before ankle or hip flexion become your limiting factor.

Resistance Profile

The barbell squat is overloaded at the bottom of the rep, in the lengthened position for the quads and hip extensors. While we can shift it slightly by utilizing bands or chains, those can add degrees of complexity and coordination needed to perform this movement.

Training Stimuli

Overloading the lengthened position of a muscle increases the potential for creating mechanical damage when taken close to failure and/or at higher volumes. This will affect the frequency with which you can train the quads and hip extensors as mechanical damage is one of the stimuli that takes relatively longer to recover from. To learn more about mechanical damage, read this article:

Mechanical Damage & Hypertrophy

Due to the large amount of tissue recruited in the squat (quads, glutes, adductors, etc.) it can be very systemically taxing. If your goal is improving systemic conditioning (cardiovascular, cardiorespiratory, liver metabolism of metabolic byproducts, etc) this can be a useful tool. For more on systemic training read this article:

Set & Rep Methods: Systemic Super Sets

Safety

The safety consideration for the barbell squat is making sure to respect your active range of motion for hip flexion. This means maintaining a neutral spine and not letting your spine begin to round or pelvis tilt at the bottom. This is the primary cause of injury in the barbell squat.

Because the squat does require a relatively high degree of coordination, taking it to the same degree of failure as a more isolated and stable exercise (like the leg extension) is extremely challenging. Depending on what tissue you’re using the squat for predominantly (quads, glutes, adductors), other tissues may reach failure first, limiting the maximum potential stimulus you can get from this exercise for the target tissue.

Fatigue may lead to a degradation in execution, increasing the risk of injury in those who have not mastered the ability to maintain their execution at high intensities and degrees of fatigue.

Other Considerations

The spine is also loaded in the barbell squat, which means there is demand placed on the spinal stabilizers like the erectors. This can affect what other exercises you choose in the rest of your program and how frequently you can use them. For example, doing a barbell squat followed by an RDL may decrease the load and volume you can tolerate in the RDL due to the fatigue of the spinal stabilizers.They may be the limiting factor rather than the hip extensors you’re trying to train with the RDL.

For more information on the barbell squat, check out the following pieces of content:

How to Determine Full Squat Depth

Leg Extension

Range of Motion

The leg extension will be the most isolated to the quadriceps as there is no hip movement. It will provide work in the fully shortened position in a way no other knee extension exercise provides.

Resistance Profile

Because it predominantly trains and overloads the short position, the leg extension is one of the top choices for metabolic programs. You can take it to a higher degree of fatigue and greater volume of work with less mechanical damage compared to most any other quad exercise.

Safety

The leg extension is a very safe place to work hard. So long as you’re following a proper tempo and not bouncing out of the bottom or failing to control the eccentric, you’re unlikely to harm yourself. You can literally keep working until you can no longer move.

Because your foot is essentially floating, the knee stability is limited especially in the lengthened position. So it’s best to adjust your resistance, intent, and tempo to get most of your work done in the short position for the leg extension.

This means it is not a great exercise for mechanical damage stimuli on it’s own. But when used as a pre-exhaust before something that trains the lengthened position (like the barbell squat), it is a brutal combination.

Other Considerations

The leg extension is about as isolated and stable of a quad exercise as it gets, making it a great choice for training the quads to a high degree of fatigue without other tissues or breakdown in execution becoming the limiting factor.

It can easily be paired with most other quad exercises to create a variety of super sets for various stimuli. Because the leg extension and barbell squat are essentially opposite in their resistance profiles, they can be a great compliment to one another in a program to maximally tax the quads through a greater range of motion than either can on its own.

Intro to Resistance Profiles & Strength Profiles

videoAnatomy & Biomechanics Definition Foundation FREE SupportWhy Training the Shortened and Lengthened Position of a Muscle Matters

videoAnatomy & Biomechanics Foundation Training

Popular Pages

Learn & Train With Us

Add N1 Training to your Homescreen!

Please log in to access the menu.