Muscle Damage & Hypertrophy

n1 training

What role does muscle damage play in the quest for muscle hypertrophy?

First, what exactly is it and how does it occur?

It was once thought that creating high amounts of tension within a muscle, especially through an eccentric movement (lengthening of the muscle under load), or any time we take a set very close to failure would result in some degree of microtrauma in the muscle tissue.

In light of more recent research, it appears that the damage that occurs is a result of an inflammatory response rather than mechanical tension itself. The two primary culprits seem to be the influx of calcium ions, which can be influenced by training lengthened positions for muscles, and oxidative stress. The degree to which we experience either one of these can be affected by the type of training program.

Is It A Tool, Or “Collateral Damage” To Be Minimized?

In the evidence-based fitness community, there is a popular position that mechanical damage should not be the goal of training for muscle growth. This is based on the conclusions drawn in some studies that show hypertrophy from programs that induce higher amounts of muscle damage is similar to programs that minimize mechanical damage but still contain high amounts of tension. [1]

If we are looking at only cross-sectional areas in a relatively short time-frame and a single program, this is a perfectly reasonable conclusion.

But there is some contextual information that is left out, which is critical to understanding the potential value of intentionally performing a program focused on inducing mechanical damage…

The biological adaptations on a cellular level.

New muscle tissue is not the only adaptation that occurs from resistance training.

When cellular damage is induced, there are also adaptations that occur within those cells. The two most prominent are:

- Satellite cell recruitment

- Lysosome biogenesis

Satellite Cells

You may have heard about satellite cells before. They are essentially “blank” cells that sit near the sarcolemma. When damage occurs to a significant degree, a signalling effect takes place that recruits these nearby cells to come and donate their contents to the cell in need of repair. Namely their nucleus.

This results in an increase in what is known as “myonuclear domain”, or the number of nuclei within a cell. While this does not immediately lend to an increase in muscle mass (other than the mass of the nuclei themselves), what it DOES do is increase that cell’s potential rate of recovery and repair from future trauma. [2]

Yes, it literally means you can recover faster from training and build new muscle tissue more quickly.

Sounds like a pretty valuable adaptation, right?

Lysosome Biogenesis

When damage is created within a cell, something has to clean up those damaged proteins and other waste products. This is where an organelle called a lysosome comes in. It “cleans up” and breaks down those damaged proteins back into amino acids that can then be used by the cell to build new tissue or perform any number of other processes. They do much more, but for our purposes we’ll just focus on those functions.

They are sort of like the recycling crew of your cells.

When significant damage occurs and the existing lysosomes cannot “keep up” with the demand, it can induce biogenesis (one lysosome splits itself into two). When you have more lysosomes, your cells can then “clean up” waste faster and resume repair more quickly.

Again, this doesn’t result in an immediate growth in muscle tissue, but it expedites the potential rate of recovery for the future.

Big Picture Value

Neither of these two adaptations from mechanical damage to muscle tissue results in a significantly greater increase in hypertrophy compared to tension work in the short term. However, long-term these adaptations can allow you to recover more quickly from both any future cellular trauma and allow for faster protein synthesis from tension-based stimuli for muscle growth.

This is why at N1, we don’t discount mechanical damage as something to be absolutely avoided. We may intentionally design a short-term program focused on inducing it in order to obtain the cellular adaptations mentioned above. We use it as a tool for potentiation of recovery and hypertrophy in future programs.

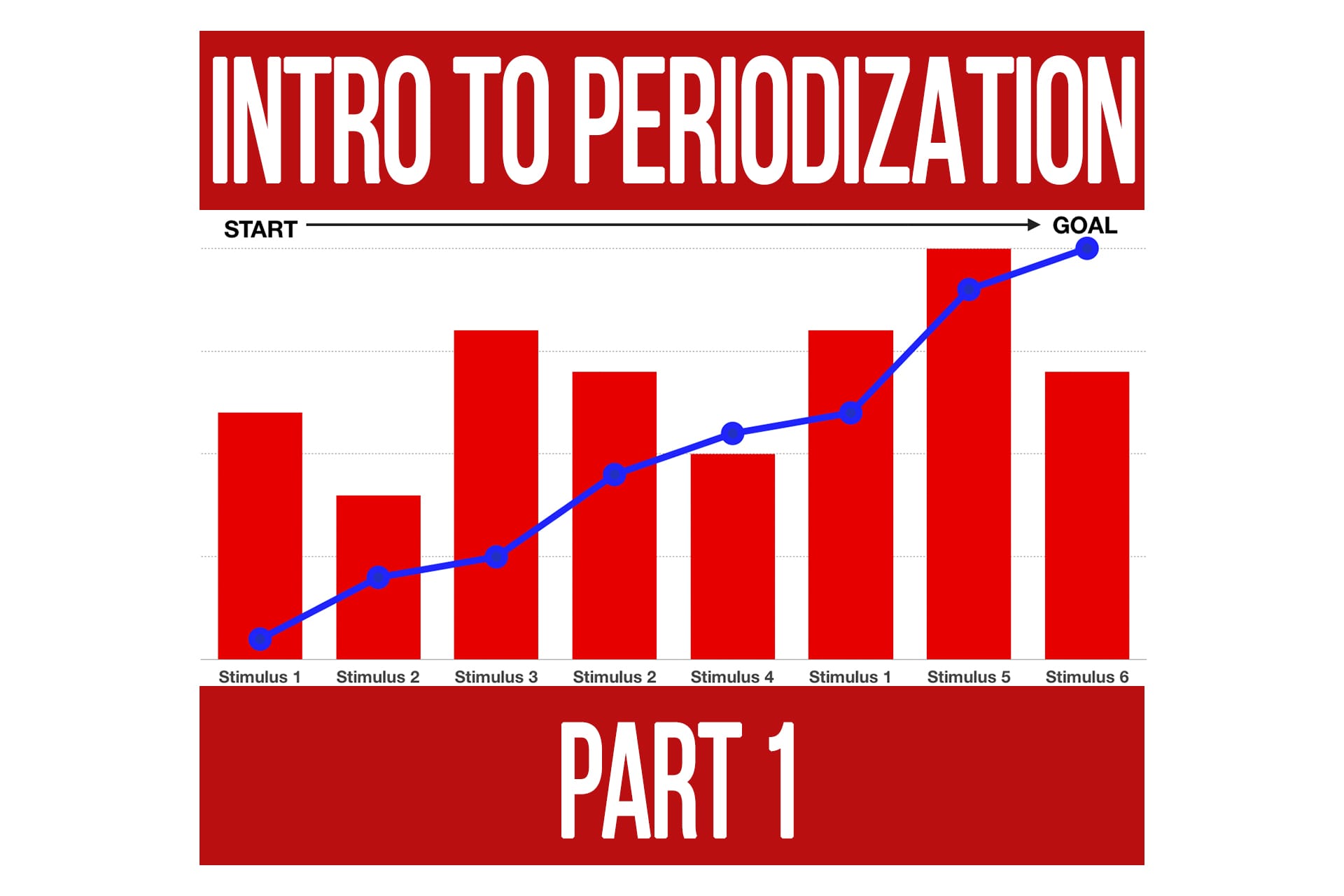

That being said, there are also times during many other programs where we intentionally try to limit or minimize potential mechanical damage. This is where understanding all training variables when designing programs and how to periodize stimuli becomes critical.

The Punchline

Mechanical damage is not evil and has value when used intelligently. It is a tool that should be employed appropriately as a part of a long-term periodized hypertrophy plan. When looking at research, it is important to look beyond just the conclusions of the authors but put it in context of all available information.

If you’d like to learn more about program design for hypertrophy (or any other goal), consider joining us for the Nutrition & Program Design course where we walk you through everything from biology to writing workouts for specific stimuli and how to match nutrition correctly.

Citations

[1] Damas, F., Libardi, C.A. & Ugrinowitsch, C. The development of skeletal muscle hypertrophy through resistance training: the role of muscle damage and muscle protein synthesis. Eur J Appl Physiol 118, 485–500 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-017-3792-9

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-017-3792-9

[2] Schoenfeld, Brad J. Does Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage Play a Role in Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy?, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: May 2012 – Volume 26 – Issue 5 – p 1441-1453 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31824f207e

What role does muscle damage play in the quest for muscle hypertrophy?

First, what exactly is it and how does it occur?

It was once thought that creating high amounts of tension within a muscle, especially through an eccentric movement (lengthening of the muscle under load), or any time we take a set very close to failure would result in some degree of microtrauma in the muscle tissue.

In light of more recent research, it appears that the damage that occurs is a result of an inflammatory response rather than mechanical tension itself. The two primary culprits seem to be the influx of calcium ions, which can be influenced by training lengthened positions for muscles, and oxidative stress. The degree to which we experience either one of these can be affected by the type of training program.

Should We Always Try To Minimize It?

In the evidence-based fitness community, there is a popular position that muscle damage should never be the goal of training for muscle growth. This is based on the conclusions drawn in some studies that show hypertrophy from programs that induce higher amounts of muscle damage is similar to programs that minimize muscle damage but still contain high amounts of tension. [1] The reasoning is that because recovery from muscular trauma takes significantly longer, minimizing it will allow you to train more frequently and build muscle faster.

If we are looking at only cross-sectional areas in a relatively short time-frame and a single program, this is a perfectly reasonable conclusion.

But there is some contextual information that is left out, which is critical to understanding the potential value of intentionally performing a program focused on inducing muscle damage…

The biological adaptations on a cellular level.

New muscle tissue is not the only adaptation that occurs from resistance training.

When cellular damage is induced, there are also adaptations that occur within those cells. The two most prominent are:

- Satellite cell recruitment

- Lysosome biogenesis

Satellite Cells

You may have heard about satellite cells before. They are essentially “blank” cells that sit near the sarcolemma. When damage occurs to a significant degree, a signaling effect takes place that recruits these nearby cells to come and donate their contents to the cell in need of repair. Namely their nucleus.

This results in an increase in what is known as “myonuclear domain”, or the number of nuclei within a cell. While this does not immediately lend to an increase in muscle mass (other than the mass of the nuclei themselves), what it DOES do is increase that cell’s potential rate of recovery and repair from future trauma. [2]

Yes, it literally means you can recover faster from training and build new muscle tissue more quickly.

Sounds like a pretty valuable adaptation, right?

Lysosomal Biogenesis

When damage is created within a cell, something has to clean up those damaged proteins and other waste products. This is where an organelle called a lysosome comes in. It “cleans up” and breaks down those damaged proteins back into amino acids that can then be used by the cell to build new tissue or perform any number of other processes. They do much more, but for our purposes we’ll just focus on those functions.

They are sort of like the recycling crew of your cells.

When significant damage occurs and the existing lysosomes cannot “keep up” with the demand, it can induce biogenesis (one lysosome splits itself into two). When you have more lysosomes, your cells can then “clean up” waste faster and resume repair more quickly.

Again, this doesn’t result in an immediate growth in muscle tissue, but it expedites the potential rate of recovery for the future.

Big Picture Value

Neither of these two adaptations from damage to muscle tissue results in a significantly greater increase in hypertrophy compared to tension work in the short term. However, long-term these adaptations can allow you to recover more quickly from both any future cellular trauma and allow for faster protein synthesis from tension-based stimuli for muscle growth.

This is why at N1, we don’t discount damage as something to be absolutely avoided. We may intentionally design a short-term program focused on inducing it in order to obtain the cellular adaptations mentioned above.

We use it as a tool for potentiation of recovery and hypertrophy in future programs.

That being said, there are also times during many other programs where we intentionally try to limit or minimize potential damage. This is where understanding all training variables when designing programs and how to periodize stimuli becomes critical.

The Punchline

Muscle damage is not evil and has value when used intelligently. It is a tool that should be employed appropriately as a part of a long-term periodized hypertrophy plan. When looking at research, it is important to look beyond just the conclusions of the authors but put it in context of all available information.

If you’d like to learn more about program design for hypertrophy (or any other goal), consider joining us for the Nutrition & Program Design course where we walk you through everything from biology to writing workouts for specific stimuli and how to match nutrition correctly.

DOMS Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness – What Can It Tell Us?

articleDefinition Foundation FREE Hypertrophy Support

Popular Pages

Learn & Train With Us

Add N1 Training to your Homescreen!

Please log in to access the menu.