Training Volume is Not a Simple Math Equation

n1 training

Training Volume is Not a Simple Math Equation

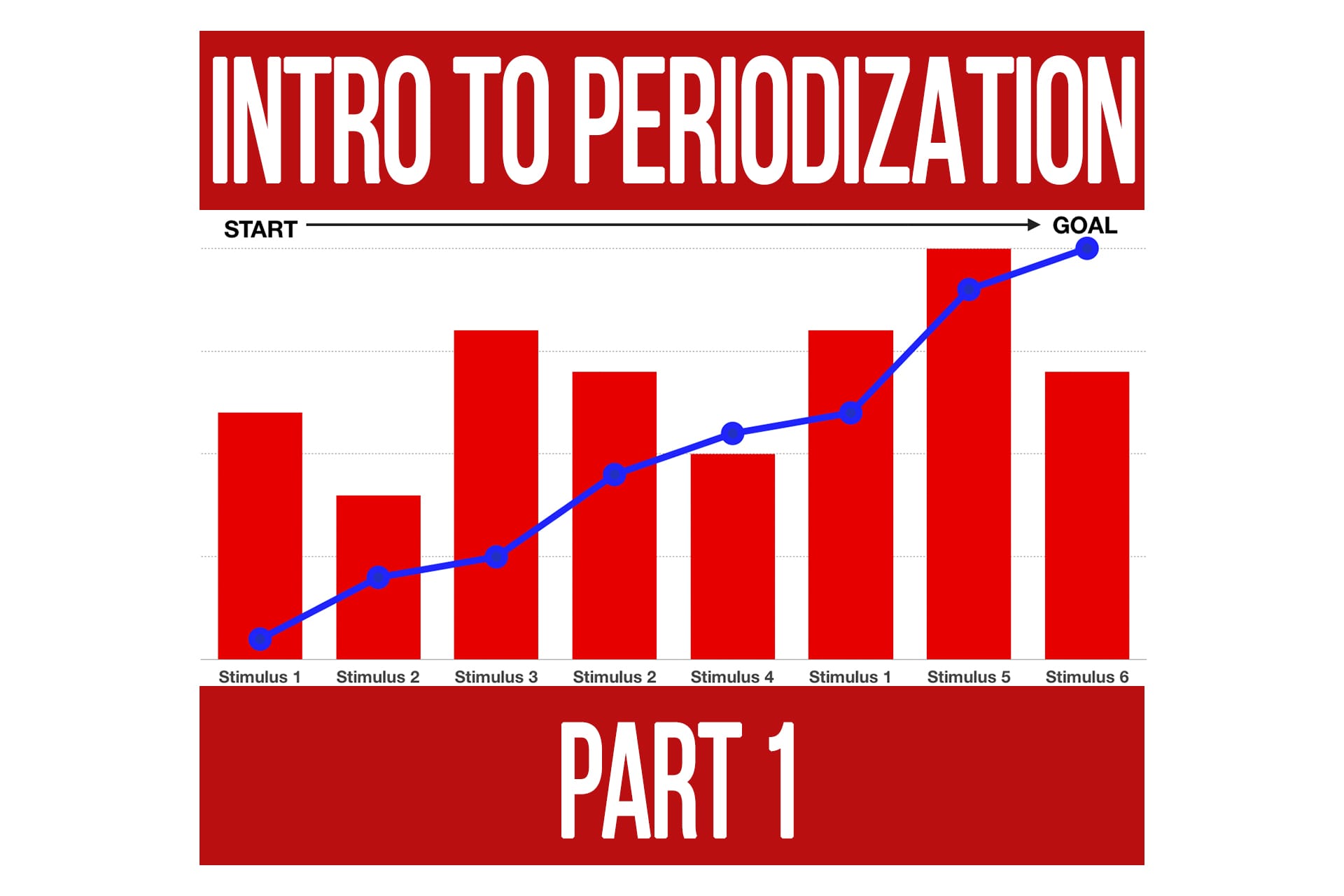

If you’ve been working out for a while, especially if focusing on strength or muscle gain, you’re probably familiar with the concept of training volume. Likely you have heard or been taught that progressive overload by increasing training volume over time is the only surefire way to get stronger or add muscle tissue.

In an overly simplified sense, that is correct. However, we’re going to dive a bit deeper into why calculating training volume is not as easy as many people think.

When first introduced to the concept of training volume, it is usually boiled down to calculating total tonnage, or the total amount of weight moved.

Weight x Reps = Volume (total weight moved)

On the surface that seems reasonable if you were to calculate this for every body part and then try to increase that “volume” number from week to week.

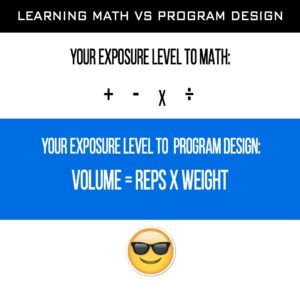

For the purpose of this article let’s use the analogy of learning math to learning how to calculate for volume.

The basic equation above is like when all you know about math is +, -, x,

But what we should really be trying to estimate the volume of is the volume of the training stimulus we’re trying to achieve.

Let’s say you compared a chest press for 5 sets of 10 reps with 50lb dumbbells with 4 sets of 25 reps with 25lb dumbbells. Both of them are 5,000 pounds of “volume”. But you know that it is a very different outcome of how your chest feels at the end of each set and by the end of the last set.

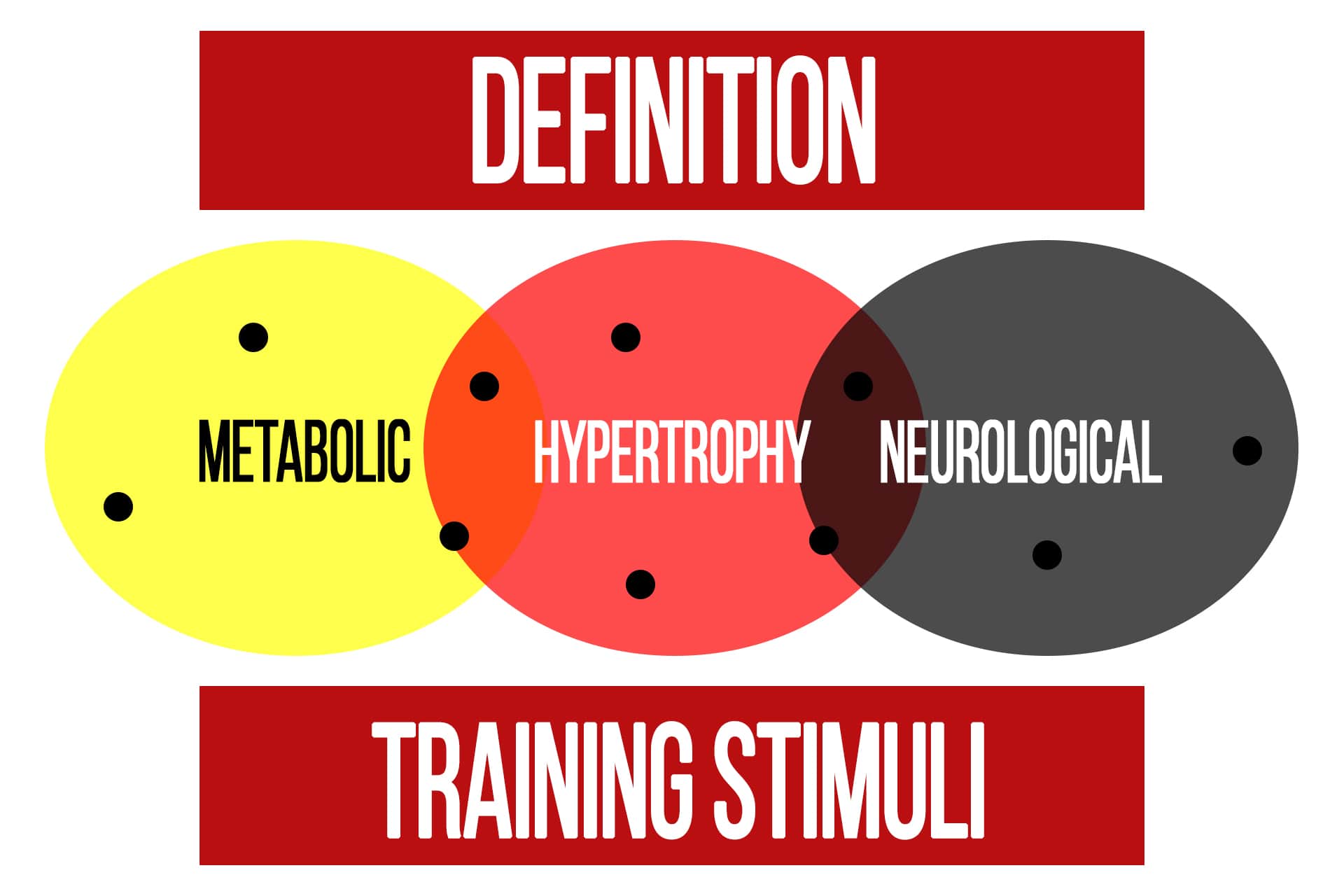

Those are two different types of stimuli for the muscle tissue. Keep that in the back of your mind for now and we’ll come back to it soon.

Now let’s look at some of the real-world variables that make that number less reliable for the purpose of progressive overload.

Level 2

Exercise Selection: Different exercises can train a muscle at different lengths. For example an incline cable curl (fully lengthened position of the biceps) and a high cable curl (shortened position of the biceps). Even if you used the same load and total number of reps for these exercises you can feel that they are very different in the stimulus you create for the biceps. Training a muscle in its lengthened position is the easiest place to create mechanical damage. That is neither good nor bad, just depends if that is the goal of the workout or not. This is why choosing exercises that compliment your training goal is important. But yet, this is not factored into the basic “Volume” equation.

To learn more about the importance of exercise selection based on your goal, we have two videos that introduce the concepts to consider:

Exercise Selection for High Frequency Training

Importance of Understanding Exercise Selection

Another consideration is the mechanical advantage of the exercise you’re using. If we compared a cable lat pulldown to a plate loaded pulldown (like Hammer Strength or Arsenal brands for example), the loads used on those two exercises are not directly comparable. If you put 90 pounds on both the weight stack and the weight horns of the plate loaded machine one might feel significantly more challenging either throughout the range or a part of the range. Even if we compared two plate loaded pulldowns with different lengths of arms where the plates are loaded (such as Hammer vs Arsenal brand) the same amount of weight will be a drastically different challenge. If one machine is more challenging throughout the range of motion than another, even though you have the same amount of weight on them, is it the same amount of muscular work? Of course not.

Range of Motion: Moving a load over a greater distance is more work done in the physics sense. In the basic equation a squat and a leg press would be essentially the same, even though the ROM of a leg press is about ½ that of a squat. As I’m sure you know, you can do a TON more “weight” loaded onto the leg press than a squat. So if the only thing that contributed to muscle gain was moving more weight for reps, everyone would just leg press. Intuitively though, you know that doesn’t make much sense.

For more on ROM, check out the following pieces of content:

Resistance Profile: Exercises vary in resistance profile. This means that while one exercise might be very hard in a small portion of the range and relatively easy through the rest (Squat, preacher curl, etc) another exercise for the same muscle group might be challenging through a greater portion of the range. So would those two exercises contribute equally to volume of work done by the muscle? No, but the basic formula would say they are the same.

Next we will consider training variables and how they can affect volume based on what we’ve talked about above.

Level 3

Tempo: Tempo has a massive influence on the effect a rep or set has on the muscle(s) we’re training and the stimulus we are trying to achieve. If you are not familiar with reading tempo, please refer to the article Understanding Tempo. (If you aren’t using tempo in your workouts I HIGHLY recommend you start ASAP).

Just compare a squat with a 3010 tempo (3 second eccentric immediately into a 1 second concentric) to a squat with a 3210 tempo, which is adding a 2 second pause at the bottom of that squat. Pretty significant difference in the amount of work for your quads and glutes, right? There’s no accounting for tempo in the traditional volume equation.

It’s not just about “time under tension” (TUT) either. It’s about time under significant tension (TUST). The amount of work added to a rep with the tempo must also be paired with the resistance profile of an exercise. Spending time where the exercise is hardest (where there is significant tension) is DRASTICALLY different than pausing where there is little to no tension. For example, using a 3012 tempo on a squat may be considered more time under tension because each rep takes longer, but during those 2 seconds at the top there is minimal (if any) tension on your quads and glutes because the load is just stacked on your spine and joints.

Changing the tempo or even using it as a method of progression in a well-designed program can have a massive influence on the stimulus created within each set and for the overall workout. There is much more we can dive into with tempos, but it is beyond the scope of this article. (Teaser: the tempo you use can change the resistance profile of an exercise)

Rest Periods: Remember the dumbbell example from earlier? Ok good. So we already saw that the same amount of weight moved can result in very different stimuli depending on how the sets and reps are programmed. Now let’s discuss factoring in rest periods.

Changing the rest period may allow you to use more or less weight for the same number of sets and reps. However, you might be getting a greater degree of a metabolic stimulus. A perfect example of this is the incomplete rest method. It’s highly effective for achieving a local metabolic stimulus but might not seem like much “volume” compared to using a longer rest period.

Let’s say you progressed your workout by decreasing the rest periods a little and were able to maintain the same weight. You technically made your workout more dense and have increased the metabolic stimulus of that exercise or super set (depending how your workout is structured). Your “reps x weight” number stayed the same, but you increased the stimulus achieved, which means you made progress from the last workout.

Still with me so far? I know it can be a lot to take in, especially if you are newer to some of these concepts. But just like any skill, it takes practice to get really good at this stuff. It’s also why we try to take care of some of the more complex things like proper progressions and volumes for different stimuli in the workout programs.

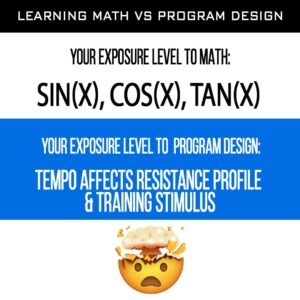

So now, with the addition of tempo and rest periods in our math analogy, you’ve now graduated to trigonometry!

Just like in trig, there can be multiple solutions to an equation (more than one way to achieve a stimulus when writing a workout) and there are some points that just don’t exist in certain equations (certain set/rep schemes that just don’t go with some stimuli).

Yes, I know I’m a nerd for making this math analogy. But hopefully you’re a bit of a fitness nerd too and want to make the most of your training by learning some of these important concepts 🙂

Now, on to the part that REALLY messes with the whole “volume” tracking fetish that some people get caught up in.

Level 4

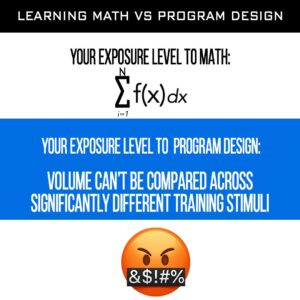

Volume Cannot Be Equated Across Different Stimuli

I’d suggest reading that again carefully.

This is probably the most important thing to know, especially when working with a physique based goal. This is because when training for physique changes, you likely will (and should) be using different training stimuli across a long-term periodized plan. When switching stimuli you cannot base your volume calculations on the previous program.

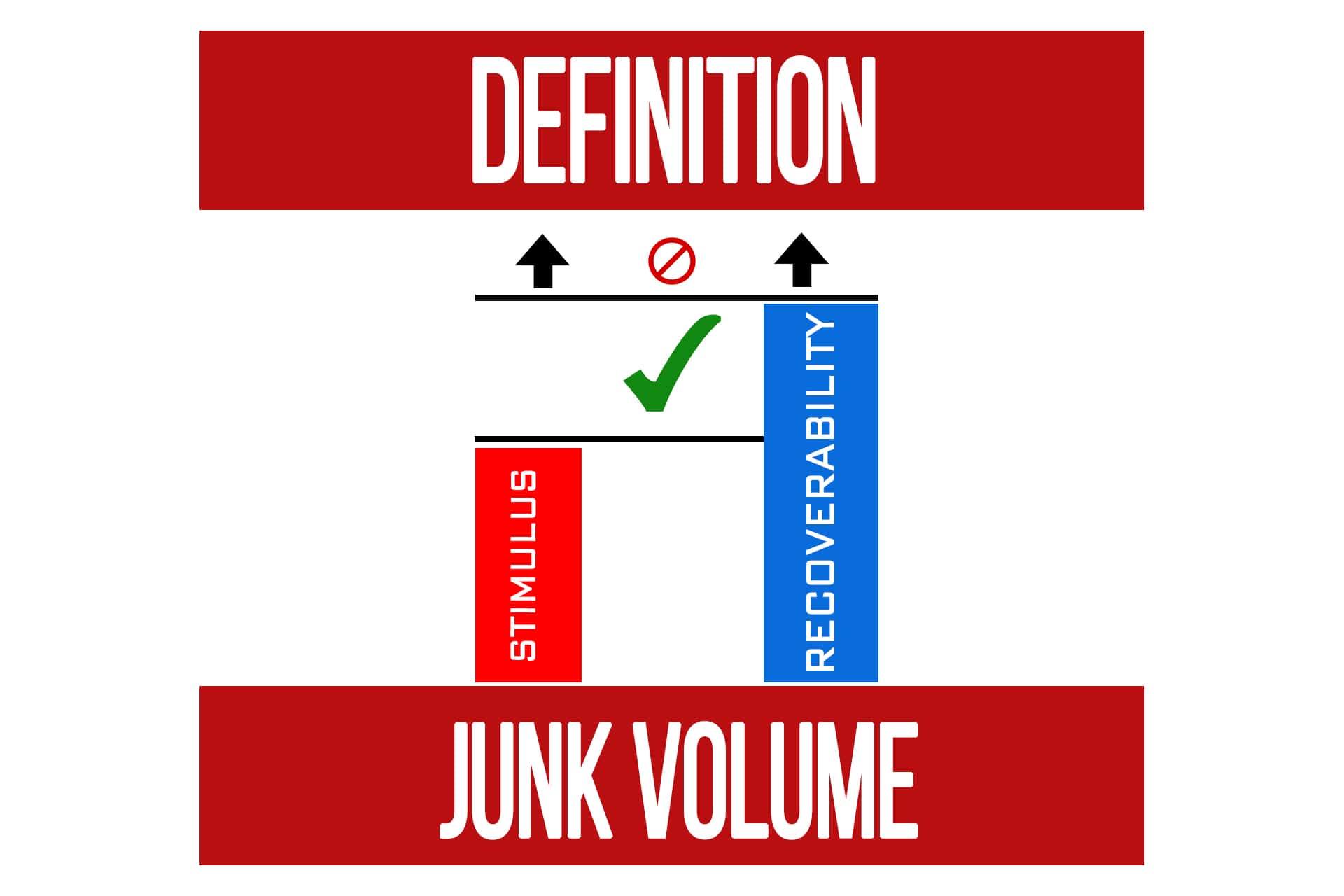

One of the main reasons for this is what we refer to as trainability. This is the difference between an individual’s ability to stimulate a particular adaptation and recover from the amount of work required to trigger that adaptation.

An example would be systemic conditioning. One person might have a great ability to continue working at a moderate intensity over a given period of time while another person, working at the same relative intensity, might drop off in performance very quickly due to cardiovascular or energy production limitations. This is where the N of 1 principle is most prevalent.

And we haven’t even talked about how level relative effort and failure (RPE, RIR) factors in….

Summary

Volume has to be determined and progressed PER STIMULUS.

There are multiple factors that influence the volume of work done that contributes to a particular stimulus that extends far beyond the total amount of weight moved.

Volume can be estimated, but the equation to do so is much more complicated than what is commonly used.

Progressive overload is a very valuable part of getting results for strength, muscle gain, and even fat loss or athletic performance but there is much more to consider than just the amount of weight used.

If you’d like to increase your knowledge of training volume we now have an online course dedicated to teaching both the fundamentals and advanced considerations of progressive overload.

Topic Course – Progressive Overload

To learn more about programming for specific training stimuli for strength, muscle gain, fat loss, and performance check out the Nutrition & Program Design course with 25 hours of lessons and another 12 hours of continued education content only available to N1 students.

If you’ve been working out for a while, especially if focusing on strength or muscle gain, you’re probably familiar with the concept of training volume. Likely you have heard or been taught that progressive overload by increasing training volume over time is the only surefire way to get stronger or add muscle tissue.

In an overly simplified sense, that is correct. However, we’re going to dive a bit deeper into why calculating training volume is not as easy as many people think.

The Basic Traditional Formula

When first introduced to the concept of training volume, it is usually boiled down to calculating total tonnage, or the total amount of weight moved.

Weight x Reps = Volume (total weight moved)

On the surface that seems reasonable if you were to calculate this for every body part and then try to increase that “volume” number from week to week.

For the purpose of this article let’s use the analogy of learning math to learning how to calculate for volume.

The basic equation above is like when all you know about math is +, -, x,

Let’s call this a Level 1 understanding.

Seems pretty simple and straightforward right?

But what we should really be trying to estimate the volume of is the volume of the training stimulus we’re trying to achieve.

Let’s say you compared a chest press for 5 sets of 10 reps with 50lb dumbbells with 4 sets of 25 reps with 25lb dumbbells. Both of them are 5,000 pounds of “volume”. But you know that it is a very different outcome of how your chest feels at the end of each set and by the end of the last set.

Those are two different types of stimuli for the muscle tissue. Keep that in the back of your mind for now and we’ll come back to it soon.

Now let’s look at some of the real-world variables that make that number less reliable for the purpose of progressive overload.

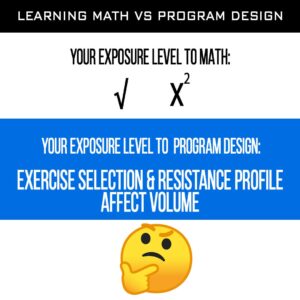

Level 2

Exercise Selection: Different exercises can train a muscle at different lengths. For example an incline cable curl (fully lengthened position of the biceps) and a high cable curl (shortened position of the biceps). Even if you used the same load and total number of reps for these exercises you can feel that they are very different in the stimulus you create for the biceps. Training a muscle in its lengthened position is the easiest place to create mechanical damage. That is neither good nor bad, just depends if that is the goal of the workout or not. This is why choosing exercises that compliment your training goal is important. But yet, this is not factored into the basic “Volume” equation.

To learn more about the importance of exercise selection based on your goal, we have two videos that introduce the concepts to consider:

Exercise Selection for High Frequency Training

Importance of Understanding Exercise Selection

Another consideration is the mechanical advantage of the exercise you’re using. If we compared a cable lat pulldown to a plate loaded pulldown (like Hammer Strength or Arsenal brands for example), the loads used on those two exercises are not directly comparable.

If you put 90 pounds on both the weight stack and the weight horns of the plate loaded machine one might feel significantly more challenging either throughout the range or a part of the range. Even if we compared two plate loaded pulldowns with different lengths of arms where the plates are loaded (such as Hammer vs Arsenal brand) the same amount of weight will be a drastically different challenge. If one machine is more challenging throughout the range of motion than another, even though you have the same amount of weight on them, is it the same amount of muscular work? Of course not.

Range of Motion: Moving a load over a greater distance is more work done in the physics sense. In the basic equation a squat and a leg press would be essentially the same, even though the ROM of a leg press is about ½ that of a squat. As I’m sure you know, you can do a TON more “weight” loaded onto the leg press than a squat. So if the only thing that contributed to muscle gain was moving more weight for reps, everyone would just leg press. Intuitively though, you know that doesn’t make much sense.

For more on ROM, check out the following pieces of content:

Resistance Profile: Exercises vary in resistance profile. This means that while one exercise might be very hard in a small portion of the range and relatively easy through the rest (Squat, preacher curl, etc) another exercise for the same muscle group might be challenging through a greater portion of the range. So would those two exercises contribute equally to volume of work done by the muscle? No, but the basic formula would say they are the same.

Next we will consider training variables and how they can affect volume based on what we’ve talked about above.

Level 3

Tempo: Tempo has a massive influence on the effect a rep or set has on the muscle(s) we’re training and the stimulus we are trying to achieve. If you are not familiar with reading tempo, please refer to the article Understanding Tempo. (If you aren’t using tempo in your workouts I HIGHLY recommend you start ASAP).

Just compare a squat with a 3010 tempo (3 second eccentric immediately into a 1 second concentric) to a squat with a 3210 tempo, which is adding a 2 second pause at the bottom of that squat. Pretty significant difference in the amount of work for your quads and glutes, right? There’s no accounting for tempo in the traditional volume equation.

It’s not just about “time under tension” (TUT) either. It’s about time under significant tension (TUST). The amount of work added to a rep with the tempo must also be paired with the resistance profile of an exercise. Spending time where the exercise is hardest (where there is significant tension) is DRASTICALLY different than pausing where there is little to no tension. For example, using a 3012 tempo on a squat may be considered more time under tension because each rep takes longer, but during those 2 seconds at the top there is minimal (if any) tension on your quads and glutes because the load is just stacked on your spine and joints.

Changing the tempo or even using it as a method of progression in a well-designed program can have a massive influence on the stimulus created within each set and for the overall workout. There is much more we can dive into with tempos, but it is beyond the scope of this article. (Teaser: the tempo you use can change the resistance profile of an exercise)

Rest Periods: Remember the dumbbell example from earlier? Ok good. So we already saw that the same amount of weight moved can result in very different stimuli depending on how the sets and reps are programmed. Now let’s discuss factoring in rest periods.

Changing the rest period may allow you to use more or less weight for the same number of sets and reps. However, you might be getting a greater degree of a metabolic stimulus. A perfect example of this is the incomplete rest method. It’s highly effective for achieving a local metabolic stimulus but might not seem like much “volume” compared to using a longer rest period.

Let’s say you progressed your workout by decreasing the rest periods a little and were able to maintain the same weight. You technically made your workout more dense and have increased the metabolic stimulus of that exercise or super set (depending how your workout is structured). Your “reps x weight” number stayed the same, but you increased the stimulus achieved, which means you made progress from the last workout.

Still with me so far? I know it can be a lot to take in, especially if you are newer to some of these concepts. But just like any skill, it takes practice to get really good at this stuff. It’s also why we try to take care of some of the more complex things like proper progressions and volumes for different stimuli in the workout programs.

So now, with the addition of tempo and rest periods in our math analogy, you’ve now graduated to trigonometry!

Yes, I know I’m a nerd for making this math analogy. But hopefully you’re a bit of a fitness nerd too and want to make the most of your training by learning some of these important concepts 🙂

Now, on to the part that REALLY messes with the whole “volume” tracking fetish that some people get caught up in.

Level 4

Volume Cannot Be Equated Across Different Stimuli

I’d suggest reading that again carefully.

One of the main reasons for this is what we refer to as trainability. This is the difference between an individual’s ability to stimulate a particular adaptation and recover from the amount of work required to trigger that adaptation.

An example would be systemic conditioning. One person might have a great ability to continue working at a moderate intensity over a given period of time while another person, working at the same relative intensity, might drop off in performance very quickly due to cardiovascular or energy production limitations. This is where the N of 1 principle is most prevalent.

And we haven’t even talked about how level relative effort and proximity to failure (RPE, RIR) factors in….

Summary

Volume has to be determined and progressed PER STIMULUS.

There are multiple factors that influence the volume of work done that contributes to a particular stimulus that extends far beyond the total amount of weight moved.

Volume can be estimated, but the equation to do so is much more complicated than what is commonly used.

Progressive overload is a very valuable part of getting results for strength, muscle gain, and even fat loss or athletic performance but there is much more to consider than just the amount of weight used.

We will be releasing a full course on Progressive Overload & Volume very soon. To get updates (and a discount at launch) SIGN UP HERE

To learn more about programming for specific training stimuli for strength, muscle gain, fat loss, and performance check out the Nutrition & Program Design course with 25 hours of lessons and another 12 hours of continued education content only available to N1 students.

Have a Question on This Content?

Please Log In to Submit Your Question

Popular Pages

Learn & Train With Us

Add N1 Training to your Homescreen!

Please log in to access the menu.